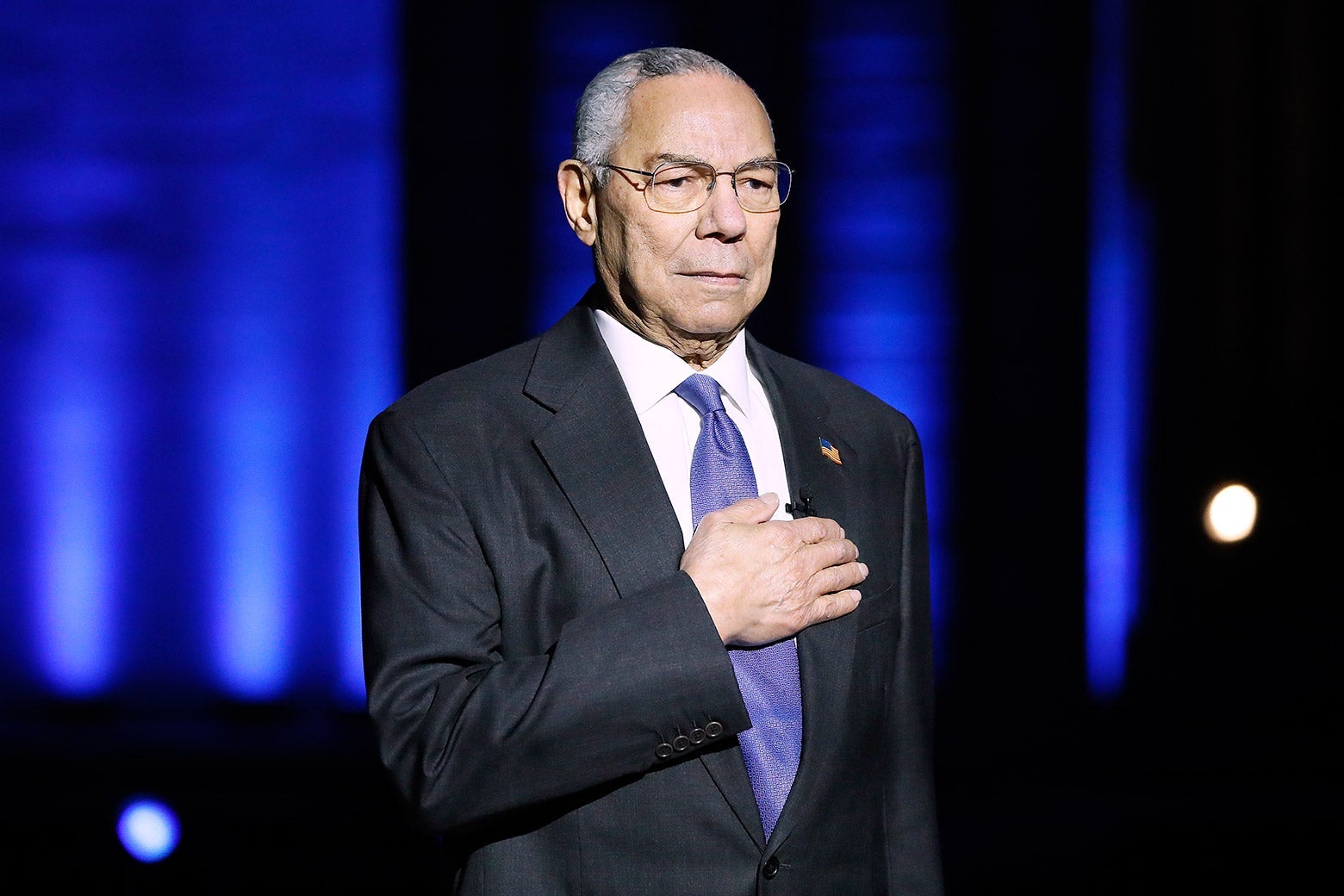

Colin Powell, the nation’s first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and secretary of state, a four-star general, and Iraq war supporter, has died from complications of COVID-19 at age 84. He was fully vaccinated. Already, right-wing pundits are using Powell’s vaccination status to question the effectiveness of vaccines and rail against mandates.

The vaccines are not perfect—particularly at preventing infection. Breakthrough infections, and even hospitalization and deaths, among vaccinated people are real. But, for people without confounding risk factors for COVID-19, the vaccines remain effective against the most serious outcomes of the disease. That is, vaccinated people who are in good health and do not have chronic conditions are very, very safe from COVID-19. The issue is that Colin Powell was not one of those people.

A crucial fact about Powell being left out of many headlines: He had been previously diagnosed with multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma is a blood cancer that devastates the immune system—in particular, the blood’s plasma cells that produce antibodies. Only 50 percent of blood cancer patients produce antibodies in response to vaccination, and even after a booster, 33 percent still fail to produce antibodies. (While it’s unclear if Powell had received a booster, and one might reasonably quibble about whether, given his age, he may need a booster to count as “fully vaccinated,” his illness, along with being 84, made him vulnerable to COVID either way.) And while we don’t know the specifics of Powell’s medical chart, he would have been at heightened risk even if his cancer was in remission. “Multiple myeloma is not curable, so while he may (or may not) have been on active treatment, his disease, and his age, made him more vulnerable to breakthrough infection, complications, and death,” said Dr. Gwen Nichols, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s chief medical officer who authored the studies I’ve linked to in this paragraph. “Myeloma is a disease which affects antibody production and immunity. Whoever transmitted the virus to him may have been asymptomatic, but they gave him a disease he could not fight as well [as people without the diagnosis], despite vaccination.”

Powell’s cohort—those who are still pretty vulnerable to the virus despite vaccination—isn’t a small slice of America. At least 1.5 million Americans are living with or in remission from multiple myeloma and related cancers. Add this number to the millions of others living with weakened immune systems, and some 10 million to 15 million people are facing down COVID without proper immunological armament. What happened to Powell is what millions of vaccinated people fear could happen to them each day, and with some good reason.

Contrary to what many are declaring, Powell’s death doesn’t illustrate the futility of vaccines—or even the need to recalibrate our understanding of how well they work—but the importance of everyone getting vaccinated to protect society’s most vulnerable. Although some may mistakenly argue that because vaccination doesn’t prevent a number of breakthrough infections, there’s no logic in getting vaccinated to protect others.

But this just isn’t true. If you’re vaccinated, you are less likely to have the coronavirus in the first place. If you do get infected, you likely carry less infectious virus and are infectious for a shorter period of time. So, yes, vaccinated people can still transmit the virus to others (and potentially get very sick, even if you are otherwise healthy). And yes, we don’t know if Powell caught the virus from a vaccinated or an unvaccinated person—but speculation about that is missing the point. Widespread vaccination, all else being equal, lowers community spread among both the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. Less spread means someone vulnerable, like Powell, would be less likely to become infected in the first place—regardless of the vaccination status of his close contacts. When combined with added precautions such as masks in crowded public spaces, vaccination remains one of the best tools we have. Powell’s death is a reminder that vaccination is an individual choice with community ramifications. Although many people with risk factors may look healthy and live healthy lives, they depend on people with stronger immune systems to protect them.