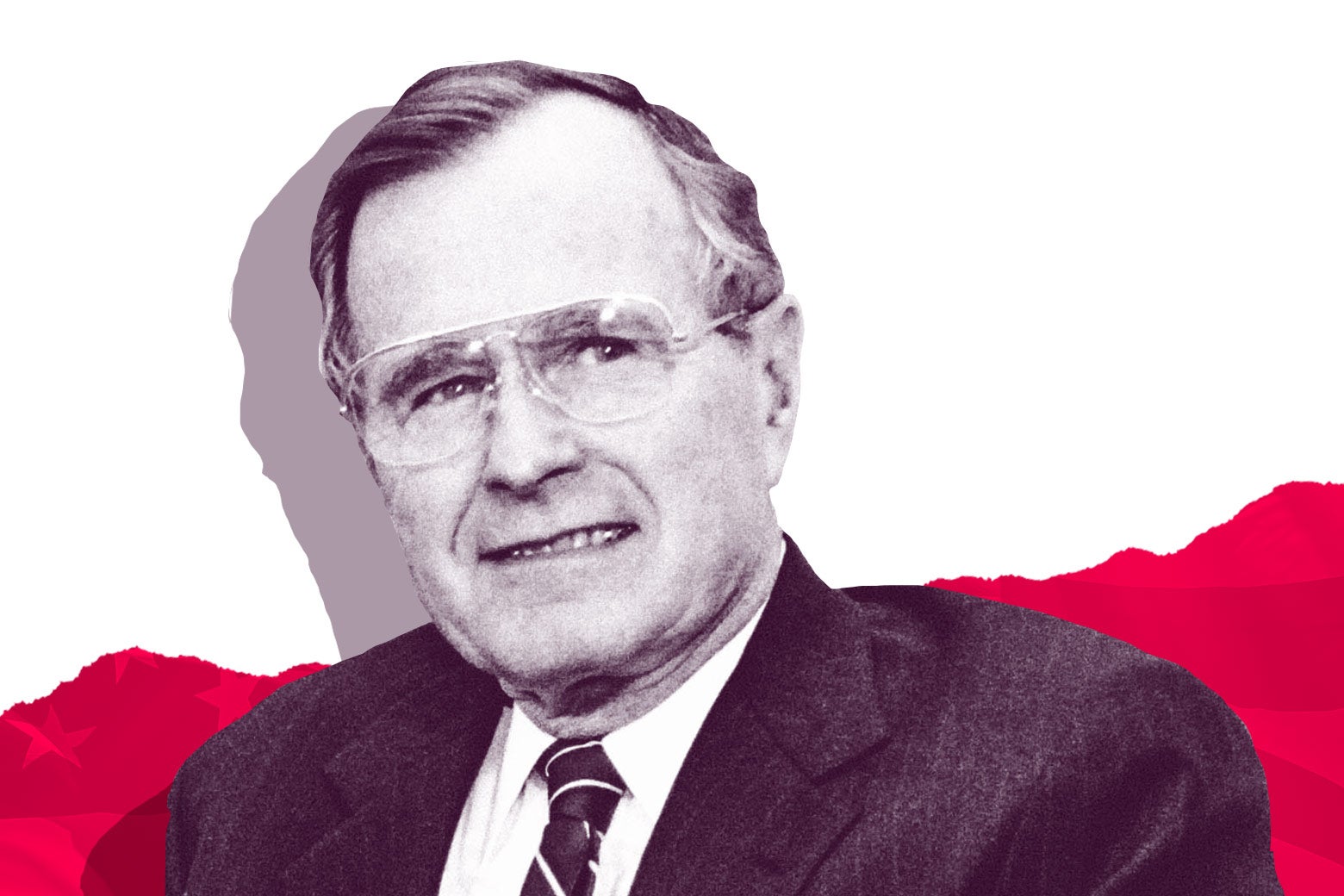

Some presidential reputations are like great red wines: They get better with time. There is no modern president about whom this is more true than the one we lost Friday, George Herbert Walker Bush. Twenty-six years ago, when he ran for re-election, Bush received the lowest percentage of the vote of any incumbent since William Howard Taft in 1912. He had been rejected by the American people and felt it. At the dawn of the Clinton years, our national memory of Bush was of an awkward, aging jogger who was throwing up sushi on state visits and seemed to be amazed by grocery checkout scanners. The impression was very unfair—especially the misreported incident at the checkout counter—but the image stuck. In comparison with Ronald Reagan, whom Bush had served as vice president for eight years, and Bill Clinton, who beat Bush with the help of the candidacy of Ross Perot in 1992, “Poppy” Bush seemed to lack the stature for 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. How wrong that impression was.

Unique among modern presidents, George H.W. Bush did not make it easy for us to appreciate him fully. When he was in office, he disdained political theater, and when his advisers forced him to do it, he was bad at it; once he left office, though he was aware of his accomplishments, he decided not to write a memoir and would not even do an official oral history for his presidential library. In a 1999 interview with the Miller Center of Public Affairs, Bush’s national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, explained the challenge of getting Bush to wax eloquent about himself and his achievements. “[H]e rejected fancy phraseology—and I used to argue with him about it … And he said, ‘That’s not me. I don’t speak that way, and I won’t give a speech that doesn’t sound like George Bush.’ So I would put little phrases in, and he’d take them out. We never did really resolve this issue as to how to do speeches.” Decades before the White House years, Dorothy Bush had taught her children to avoid using the pronoun I whenever possible because it was a sign of pride. If anything, George Herbert Walker Bush’s World War II experience deepened the aversion. Shot down by the Japanese and pulled from the churning Pacific in 1944, when he was just 20, Bush never forgot how lucky he was to have survived and never forgot about those who did not. His upbringing and life experiences made him a good, quietly confident guy but a lousy communicator in a culture that rewards self-promotion and emoting. Indeed, only earlier this year, as he led the nation in mourning for his beloved wife of 73 years, Barbara Bush, did we see the emotion that for nine decades he was trained to keep hidden.

Yet in the critical months of his time in office, arguably between October 1989 and the end of August 1991, George H.W. Bush was not just good at his job, he was great at it. The patrician World War II veteran brought the perfect mix of pragmatism, realism, and good sense to three huge challenges—the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the collapse of Reaganomics at home, and the rabid ambitions of Saddam Hussein in the Middle East—any one of which could have easily wrecked a lesser presidency. To the extent that history is a guide to such things, it was a safe bet that Moscow would not let go of its European vassals without some violence. None of the great colonial empires that collapsed in the 20th century—the French, the British, the Dutch, the Portuguese, and the Belgian—had done so without bloodshed. And those empires had faltered without possessing Moscow’s then-huge nuclear arsenal. Whatever good Reagan’s “peace through strength” policy had been in getting the world to that point—and it was Mikhail Gorbachev and the freedom movements in Eastern Europe that deserved most of the credit—it was perfectly useless as a guide to managing the last act of this drama. Meanwhile, as Marxism-Leninism was failing abroad, the consequences of Reaganomics were creating a crisis at home. A yawning budget deficit and a troubled banking sector and housing market demanded the new president’s attention. The third challenge came a year later, when Saddam Hussein sought to exploit the turmoil in world affairs by invading Kuwait in August 1990.

Bush’s skill set was extremely well-suited to the challenges of his time. What was needed was not eloquence but prudent action. After initially bobbling the Gorbachev matter—he and his team came to office wrongly assuming that the aging Reagan might have exaggerated Gorbachev’s openness to real change in Eastern Europe—Bush brilliantly managed the relationship with the maverick Soviet leader while keeping lines open to America’s nervous Western allies and its new friends in Eastern Europe. When East Germans started to tear down the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989, Bush resisted the temptation to declare victory. Even more than John F. Kennedy after the Cuban missile crisis, Bush understood that when history is going your way, it is important to turn adversaries into partners. You don’t do that by rubbing their noses in a defeat. And for Bush too, public silence was not a sign of inaction. Bush, who was also very good on the telephone and in person, worked behind the scenes. He reassured, coaxed, and led his fellow statesmen through a minefield of potential problems. The greatest of these was the question of whether or how Germany would be reunified. The first among his inner circle to embrace the idea of West Germany swallowing up East Germany with the effect that a unified Germany would be in NATO, Bush succeeded in convincing Gorbachev, Margaret Thatcher of Britain, and François Mitterrand of France that this would be in the interest of a new Europe. Then, in June 1990, he achieved the seemingly impossible, getting Gorbachev to transcend years of understandable Soviet paranoia about Germans and accept the prospect of a united Germany in NATO. Only George H.W. Bush could have done that.

Meanwhile, Bush had to manage the consequences of a failed dream at home. In the 1988 election, which was not a high point of Bush’s career, among the regrettable things that the candidate said was: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” Challenged from the right in the primaries, Bush felt he had to pretend to be more ideologically conservative than he was. Once in office, he understood that if he was to avoid letting the United States go over the “fiscal cliff” of his era—a yawning budget deficit of $221 billion and a collapsing banking sector—he would have to negotiate a budget agreement with the Democrats, who controlled Congress, and undertake an $88 billion infusion of cash to ease the pain in the housing market as one-quarter of all savings and loan associations were allowed to fail. These figures may seem quaint today, but the elder Bush paid a huge political price for his pragmatism. A young Newt Gingrich began his climb to the House speakership and sponsored the later “Contract With America” on Republican rejection of Bush’s pragmatism.

In early August 1990, Bush surprised even his inner circle by announcing, after Iraq invaded Kuwait, “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait.” Bush was determined to teach Saddam Hussein a lesson. He did not want the end of the struggle with Moscow to invite the return of the border wars that had dominated foreign affairs before the superpower nuclear contest froze many nationalist jealousies. Bush was also determined that the world, and not just the United States and its English-speaking allies, teach Saddam Hussein this lesson. Using the United Nations and patient diplomacy, helped by longtime friend and Secretary of State James Baker, Bush fashioned a real coalition of willing partners, which included the Soviet Union. Once coalition forces had thrown Iraq out of Kuwait, Bush understood that he had to bring the conflict to an end. Not only did he want small countries to learn not to use violence to resolve their disputes, he did not want his allies to take the wrong lesson from how the war ended. He asked for their help to liberate Kuwait, and once that was done, he could not ask them to do more. The Gulf War was not to be seen as an act of American imperialism. The conscious self-restraint that marked his reaction to the fall of the Berlin Wall also shaped the end of the Gulf War.

Some of this was known at the time. The elder Bush ushered in the CNN era. The challenges he faced, including the budget battle, received wall-to-wall coverage. What was underreported was the pivotal role he had played. The release of materials over the past decade—especially the oral histories done by the University of Virginia’s Miller Center—have revealed that Bush was surrounded by a team of kibitzers. They were not rivals—his was a very unified and loyal administration—but his inner circle rarely agreed. His secretary of defense, Dick Cheney, and James Baker were polar opposites on many of the foreign policy challenges he faced. Bush alone, we can now see, was the decider. Without his guidance, this administration would have been paralyzed.

Now that we understand him better, the elder Bush deserves more than to be relegated to some golden past. Some of the political nonsense we see today is the product of George H.W. Bush not getting the credit he deserved. Before the surprising ascent of Donald J. Trump, the fog machines of both political parties decided to focus on the men before and after “41.” The GOP, especially the Tea Party and other descendants of Gingrich, elevated Reagan and assigned to him the achievements of George H.W. Bush. Bush was much more than the Pope Benedict XVI to Reagan’s Pope John Paul II. Without Bush, the achievements that the Reaganites claim for themselves—the peaceful end of the Cold War and the economic prosperity of the 1990s—would not have happened. The Reagan propaganda was so strong that even Bush’s son, George W. Bush, ran and tried to govern like Reagan in what seemed to many a mistaken effort to rescue the family’s honor. In the same vein, Democrats need to keep in mind that the Clinton economic boom would have been unlikely without the fixes that the elder Bush made, at great political cost to himself, in the early years of the decade. I suspect that Clinton, who came to love and admire Bush 41, knows this, and Barack Obama, who awarded the elder Bush the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, knows it too.

Many will note, sadly, the irony that with his polar opposite in the White House, Bush leaves us at a time when leaders like him are scarce and more needed than ever. And it isn’t just the policy differences with Trump—which are enormous on matters like trade, foreign policy, immigration, collective security, the intelligence community, the environment—that will make the first Bush so missed. It is the sharp contrast in their demeanor and sense of fair play. Even those who disagreed politically with George H.W. Bush admired him for his sense of decency. Yet Bush was not perfect. Some fault him for a campaign that at the very least used racial dog whistles in 1988. And at the end of 2017, the #MeToo movement prompted credible allegations that he had inappropriately touched women in public since 2000—though he, unlike the current president, apologized.

Bush’s presidential style mirrored more than an old-fashioned Yankee upbringing. Bush not only witnessed the pain caused by extremism and intolerance in the 20th century; it shaped him. He had fought ideologies in World War II, and at the end of the Cold War, he worked day and night to help Europe peacefully divorce itself from Marxism-Leninism. When rigid right-wing ideology, this time in the form of Reaganomics, threatened the American standard of living, he did what he had to do, not for his own political well-being but because it was right. For him, pragmatism, compromise, and bipartisanship were not byproducts of weakness. They were signs of strength. Later, when gun rights advocates went too far and accused the Clinton administration of Nazi tactics after Ruby Ridge and Waco, Bush canceled his membership with the National Rifle Association. If there was an American hero in the unsettled world of the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was George H. W. Bush. And in these times, what was merely a footnote in Bush’s long public career serves as a reminder of how far our political class has come unmoored. In August 1974, when he was chairman of the Republican National Committee, Bush told Richard Nixon that, for the sake of the country, it was time to go. “The man is amoral,” Bush wrote in his diary. As a charter member of what would become known as America’s Greatest Generation, he understood to his core what putting the country first really meant. There could be no better honor paid to him now than showing a little more humility, civility, and Republican backbone in Trump’s Washington. Or, in the idiom of his mother, Dorothy Bush, less I, I, I, and more We.