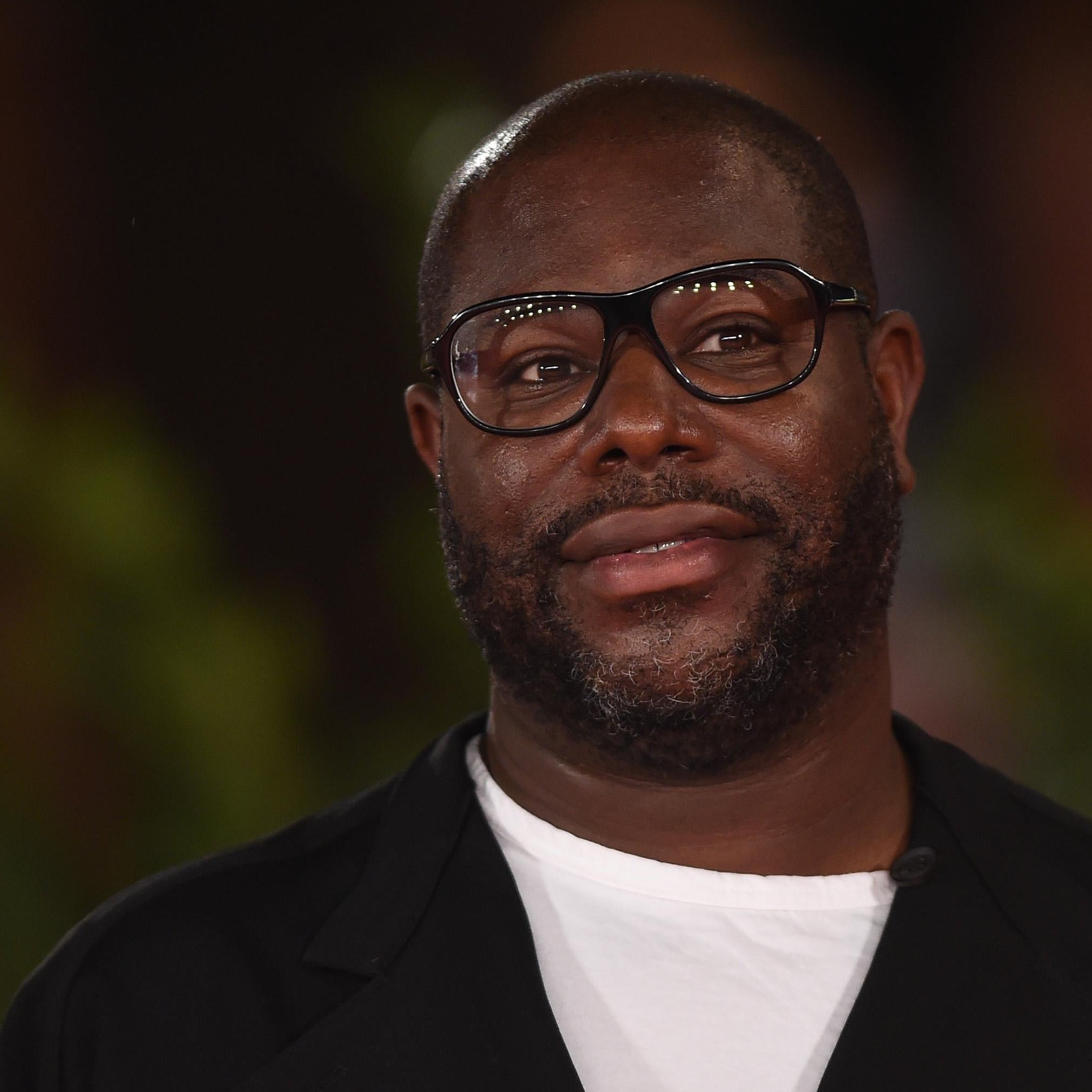

The five films in Steve McQueen’s anthology series Small Axe explore police brutality, institutional racism, and the politics of protest. But they also celebrate a vibrant West Indian immigrant culture doggedly determined to make its way in a hostile city, London from the 1960s to the 1980s. The most unabashedly sweet of the five is Lovers Rock, premiering Friday on Amazon Prime. Taking its name from the genre of romantic reggae that reigned at the turn of the 1980s, Lovers Rock tells the story of a young couple meeting and falling for each other over the course of a single all-night house party.

The reggae, dub, and disco soundtrack to Lovers Rock is also the soundtrack of its characters’ lives, hopes, and dreams. I talked through the film song by song with Steve McQueen, discussing the sound of lovers rock, the way music can serve as a refuge, and the power of a sweet falsetto.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Dan Kois: What made you want to center a movie around this time and this place, and this sound specifically?

Steve McQueen: Well, blues parties have been going on in U.K. since the 1950s. My mother went to blues parties. At that time, West Indian people, Black people, were not welcome into clubs. Therefore, people thought, “You know what? We’ll make our own.” So front rooms used to be turned into discos. People just roll up their carpets, get their couch, and a coffee table, whatever, put it in the spare room, and make that front room a venue for a club. People used to pay at the door. There used to be food cooked in the kitchen to serve, and drinks.

In the ’50s, it used to be bluebeat, prior to reggae. Then ska, and then reggae, and then dub came in. Often, the women, ladies, they weren’t keen on—they liked it, but it wasn’t a thing for them. What had to happen, in a way, was that we had to make our own sweet music. And that’s when lovers rock came in. That’s when it was so beautiful because of the vulnerability of these women and these men singing in high-toned voices about “Do you like me?,” “Do you want to hold my hand?” It became much gentler. It set the mood for the dance.

We see that in the movie. The DJ plays some hard dub, but then the first song we see people dancing to is “Darling Ooh” by Errol Dunkley. Why’d you decide to start the party with that song?

It’s almost like spraying perfume in the room, to get the mood right. I remember the men used to sort of line the walls like wallpaper, and the women who were there danced in their groups. Then, of course, the DJ would play something like “Kung Fu Fighting” and the guys would say, [butch voice] “Oh yeah. OK. We can get involved now.” Because it’s a masculine sort of pursuit, that song.

For people who are not familiar with reggae of that era, what role does the DJ toasting—chanting over the beat of the music—what role does that play in creating a party atmosphere?

Toasting sets the bar. I mean, it’s the precursor to rapping. We’ve been toasting since the late ’60s, early ’70s. It’s interesting, the development of hip-hop, and dub, and reggae, how intertwined they are. You can think of the gentleman from Jamaica who brought those speakers to the Bronx, Kool Herc. So it’s that sort of chanting, and rapping, keeping the mood, keeping the vibe. It’s the hype man. It’s like Flava Flav. He was there to hype you up.

You mentioned how when a song like “Kung Fu Fighting” comes on, everyone goes, “Oh!”

They can’t help themselves.

Exactly. One of the things I like about this movie is that the characters relate to music the way that real people do. They have their favorite songs. They sing little snippets of songs. There’s a moment early in the movie where the guys are setting up the sound system downstairs, and they play “Robin Hood Dub,” and the girls are upstairs getting ready and they hear the beat and they sing Blondie over it.

Blondie, my God.

So for these characters at this time in London, what role does music play in their lives?

It’s a refuge. Again, it’s like working-class people all over the world, you work for the weekend. Black people that time in London, you’re dealing with a lot of racist nonsense in your nine-to-five and whatnot. When you get to that blues, that blues is your time to be yourself. That blues is when you see people like you. You don’t have to explain yourself; you could be who you want to be. It’s similar to gay clubs. When you see each other, then you can be as free as you want to do.

And don’t forget, also, that blues is being circled by sharks and alligators. As we see in the film, if it’s not the police, it’s racist neighbors, it’s something. You see at the end of the party when people express themselves, it’s almost like an expelling. One expels the weight of the nonsense that one is dealing with. It’s church. It’s church in a way. It is church.

After those big, upbeat dance numbers, we see the film’s two romantic leads, Martha and Franklyn, meet while “Mr. Brown” by Gregory Isaacs is playing. Isaacs is a pretty crucial figure in lovers rock, right?

Oh my God, yeah. I mean, he’s the man, isn’t he? He was one of those men that allowed men to like lovers rock because—his appearance, he’s a dude. But he’s still talking about his feelings. He’s still talking about how he feels about this lady. The tenderness that comes out of his voice is beautiful. You didn’t often see those kinds of images of a man—particularly a Black man—and his vulnerability.

Then we have these two songs that Martha and Franklyn dance to. “After Tonight” by Junior English is romantic, and “Lonely Girl” by Barry Biggs has a sexier vibe. Can you tell me a little bit about those songs?

Well, I’m not a music historian and all of that, but [sighs] I just love them very much. And [Lovers Rock co-writer] Courttia [Newland] chose these tunes as well. It’s just—it’s a feeling, and there’s the high voice—sorry, I want to sing—[croons in falsetto] “Hey there, lonely girl …”

Where did that falsetto come from? I know for a fact a lot of Jamaican musicians were into doo-wop. Again, even Bob Marley and the Wailers, when they were called the Wailers, they were very much influenced by those kinds of men’s vocal groups.

Where you have Frankie Valli in the high register and then the other guys down below.

Exactly. It’d be interesting to find out where that came from and why that was appealing to women in a way. I have no idea. But anyway—it definitely sends me. That’s for sure. I can’t say why, but it just does it. It hits a button.

The movie’s centerpiece is “Silly Games” by Janet Kay.

Remember, this story is about my aunt. My grandmother would not allow my aunt to go to a blues. My uncle used to leave the back door open for her to sort of tiptoe out to go to dance. Then, in the morning, she had to go to church. I knew I had my narrative. That was my story. I knew that. And the song that was really the anthem of that time was, for me, “Silly Games.” It just said so much. Again, the vulnerability, you know the guy’s as vulnerable as her. But maybe he’s fronting to his friends or whatever. But also, the song tells the narrative of our two love interests in the picture. It’s a beautiful yearning, but also it’s everyone’s journey. Everybody wants that moment, to be free to be you, to be yourself.

Of course, the old gentlemen in the dance with a hat on is Dennis Bovell, who actually wrote and produced the song. He’s amazing. Also, he produced a lot of punk bands, including the Slits. Nice little cameo for him.

The DJ plays “Silly Games,” but then even after the song cuts out everyone at the party continues singing long afterward. How did that happen?

Oh, I was hoping, of course, that we would get to a point where people start singing. That’s why I cut the sound off. Then, they did. They jumped on it.

So it just happened organically?

Yeah. This is something you can’t coach. We wanted it, but I wasn’t going to push it. It was just beautiful. Beautiful. It’s beautiful. Beautiful.

Finally, we have the closing credit song, “Have a Little Faith” by Nicky Thomas, a totally lovely number. What’s the message of that song for people coming out of this movie?

I think it’s a celebration of who we are at our best. I think there are moments, of course, when we hit those peaks. And I keep that in the forefront of my mind. There’s trials and tribulations on our journey, unfortunately. But that’s how it is to be a human being. But keep your eye on the prize. That’s it. Yeah. Your faith. Yeah. That’s what we got.

Here’s a complete playlist of the songs in Lovers Rock: