In an effort to fulfill a long-standing promise, President Trump officially declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency on Thursday. In his wide-ranging speech announcing the effort, Trump acknowledged that solving the problem, which is connected to the deaths of more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and disproportionally devastates many of the regions he won in 2016, “will require us to address the crisis in all of its very real complexity.”

Unfortunately, Trump didn’t seem to have many ideas for how to deal with the problem’s complexity himself (the opioid commission he established months ago is set to present more details next week). The most specific his speech got was when he advocated for spending more money on educating youth to flat-out refuse drugs—an approach that’s been shown to be ineffective.

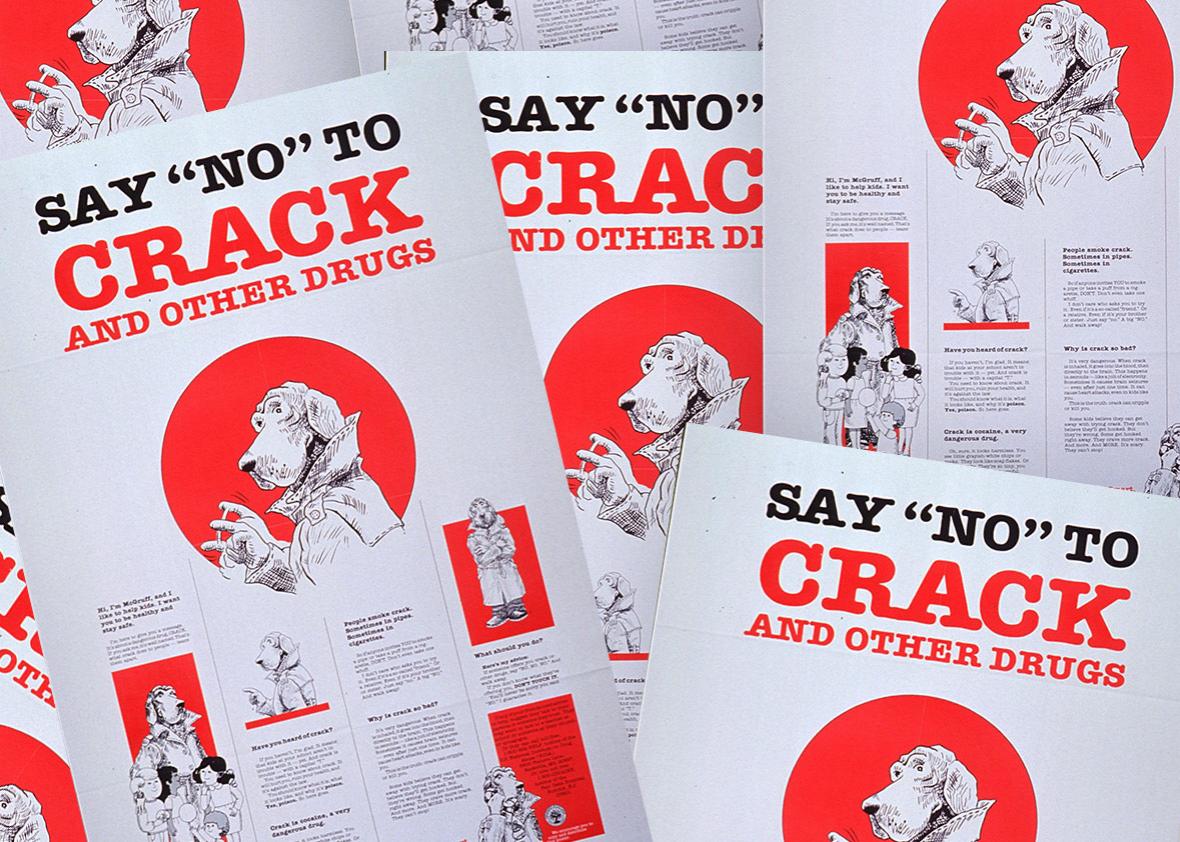

In explaining his plan, Trump invoked a lesson from his older brother, Fred Trump Jr., who suffered from alcoholism and always told Trump, who famously doesn’t drink, not to touch alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs. Speaking to a crowd of advisers, families affected by opioid addiction, and a bipartisan array of members of Congress, the most clearly articulated proposal bore a striking resemblance to Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign—Trump promised a “massive advertising campaign to get people, especially children, not to take drugs in the first place.”

From his description, this drug-abstinence campaign certainly sounds a lot like Drug Abuse Resistance Education, a program developed in the 1980s by the Los Angeles police and educators that involved officers warning students about the consequences of drug use. DARE, however, has been shown to be ineffective and sometimes counterproductive (studies published in 2002 and 2009 found that teens who participated in DARE or similar programs actually had a higher likelihood of drinking or smoking than students who hadn’t undergone the educational initiative).

According to a 2014 article in Scientific American:

Purely educational programs that involve minimal or no direct social interaction with other students are usually ineffective. Merely telling participants to “just say no” to drugs is unlikely to produce lasting effects because many may lack the needed interpersonal skills. Programs led exclusively by adults, with little or no involvement of students as peer leaders—another common feature of DARE—seem relatively unsuccessful, again probably because students get little practice saying no to other kids.

Michael McGrath pointed out another failing of moralizing messaging around drugs in The Guardian last year:

Overall, the officers’ message was simplistic and vague, grouping everything from alcohol to angel dust into one toxic cloud that loomed over our society. The demonization of such substances and those people in their orbit was of a piece with the national public service announcements of the day, which told us that drugs either made you fly or fried your brain like an egg. The end result was that, in the minds of impressionable students like myself and my classmates, drugs were a defect rather than a symptom; a moral rather than societal failure. … Much like abstinence-based sex education, Dare and “Just Say No” spread fear and ignorance instead of information, placing all responsibility on the individual while denying them the tools they need to make key decisions.

Trump echoed the sort of simplistic approach these programs apply to drug use in his speech, saying, “There is nothing desirable about drugs; they’re bad.”

Despite this resounding clarity of thought, Trump’s announcement and memorandum-signing is a bit of a disappointment. In August, the president suggested he would declare a national emergency to handle the opioid crisis, which is what his commission recommended. Instead, he declared a nationwide public health emergency, which falls under the purview of the currently vacant secretary of Health and Human Services position, instead of a national emergency. While declaring a national emergency would have released Federal Emergency Management Agency funding, declaring a public health emergency primarily just allows government workers to direct existing federal money toward the crisis. It also frees up the small Public Health Emergency Fund and allows the Department of Labor to issue dislocated worker grants for those whose employment was affected by the opioid crisis. In his speech, Trump also made vague references to educating pharmacists, taking an unnamed but “truly evil” opioid off the market, and, of course, building his border wall.

He also declared his desire to “be the generation that ends the opioid epidemic.” Unfortunately, based on the plans he’s laid out so far, it seems more likely he’ll just put another generation through an ineffective marketing campaign.