On March 26, 1953, virologist Jonas Salk announced a successful initial test of his polio vaccine. Newspaper front pages gleefully trumpeted good tidings. In 1952, polio had peaked in the U.S. with about 58,000 infections, resulting in 3,145 deaths and 21,269 cases of paralysis. As outbreaks moved from city to city, swimming pools and movie theaters closed, and parents safeguarded children at home. Salk’s announcement marked the start of the largest medical experiment ever conducted at the time, a placebo-controlled study of 1.8 million children in 44 states, carried out in 1954, that would pave the way for the near eradication of the disease.

Duon H. Miller, the cantankerous owner of a cosmetics company in Florida, was having none of it.

Under the banner of his organization, Polio Prevention Inc., Miller distributed hair-raising mailers with claims like “Thousands of little white coffins will be used to bury victims of Salk’s heinous and fraudulent vaccine.” A self-made shampoo magnate, he was one of the few malcontents who publicly campaigned against the polio vaccine. His crusade shows that even during a public embrace of the polio shot that many people frustrated at COVID anti-vaxxers have held up as the ideal reaction to a new lifesaving vaccine, there was dissent, some of it as vitriolic as that you find in the corners of Twitter that swap anti-Fauci memes and Bill Gates rants—and just as weird.

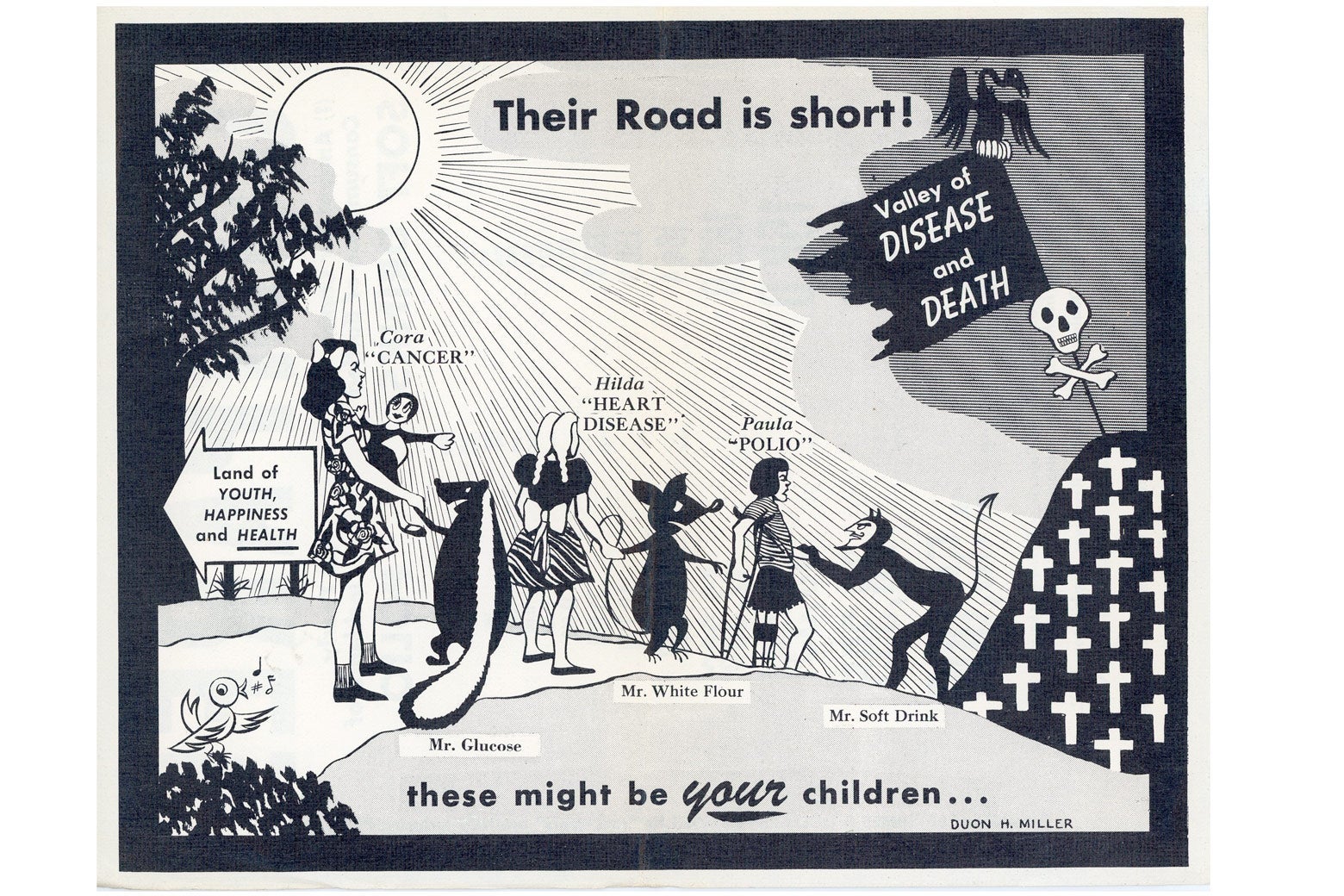

To Miller, “polio” was not an infectious disease. It was a state of malnutrition caused by midcentury American diets, particularly soft drinks—his mortal enemy. “Disease and malfunction do not ‘strike’ us; we build them within ourselves,” he wrote in one of his two-sided handbills. “Children permitted to indulge heavily in soft drinks (especially ‘colas’), over-sweetened and refined starchy foods are the greatest sufferers from POLIO. NO CHILD OR ADULT ON A COMPLETELY COMPETENT AND BALANCED DIET EVER CONTRACTS POLIO.”

“The flyers this Miller guy was sending out, a lot of it mirrors what we hear today” in the COVID anti-vax movements, said Jonathan M. Berman, a research scientist and author of Anti-Vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed Movement. “He was arguing about germ theory. We see people arguing about how coronavirus is misdiagnosed or is actually the flu or you can’t get it if you are in a certain state of health.”

To Miller, the disease wasn’t real. The conspiracy was. The “experts” were criminals. The vaccine was actually dangerous. This was your libertarian uncle’s Facebook profile, 50 years before there was Facebook. But unlike modern anti-vaxxers, Miller depended on the U.S. Postal Service—which proved, in the end, to be a more effective gatekeeper than social media has been for us.

Some facts about Duon Miller’s beginnings are murky, like why he changed his name from Donald. At times, he presented himself as a “research chemist,” and some newspapers referred to him as “Dr.” A skeptical 1954 article in the Dayton Daily News reported he had dropped out of the University of Nebraska without a degree to fight in World War I.

He founded his cosmetics company in his garage in Dayton, Ohio, according to a 1969 obituary, and grew Duon Inc. to become one of the largest shampoo manufacturers in the U.S. Its marquee product was a shampoo called Vita-fluff. Miller’s name was frequently to be found in the society sections of newspapers. He gave photography tips in the Dayton Journal-Herald and showed off boxers from his breeding pens. His first wife sang to entertain at PTA meetings in Dayton.

He was also a traveling lecturer on topics of health and beauty. In 1939, the South Bend Tribune covered “Dr.” Miller’s appearance at an Indiana beauticians convention, at which he gave an unusual explanation of the way glands work: “Complete harmony in the system of glands assures good health and a pleasant appearance. Each gland, he pointed out, has its function but can do its work only when proper diet and living conditions are available.”

Miller’s overconfidence in matters of science caused a series of spats between his business and federal regulators. They forced him to cease making fantabulous claims about the healing powers of some products, including a face cream that allegedly treated wrinkles, dark circles, double chin, psoriasis, brittle nails, and allergies. They also made him change the name of one of his companies, Northern Research Industries, because it did not conduct research.

After his second divorce, Miller moved to Coral Gables, Florida, and established a corporate headquarters there. Miller’s public speeches had included warnings about white flour and sugar. His all-out crusade against soda began in 1951, he later wrote, when his third wife was pregnant. “Our ‘quack’ M.D. advised my wife to drink ‘Cokes’ to offset morning nausea,” Miller wrote. “My blood boiled.”

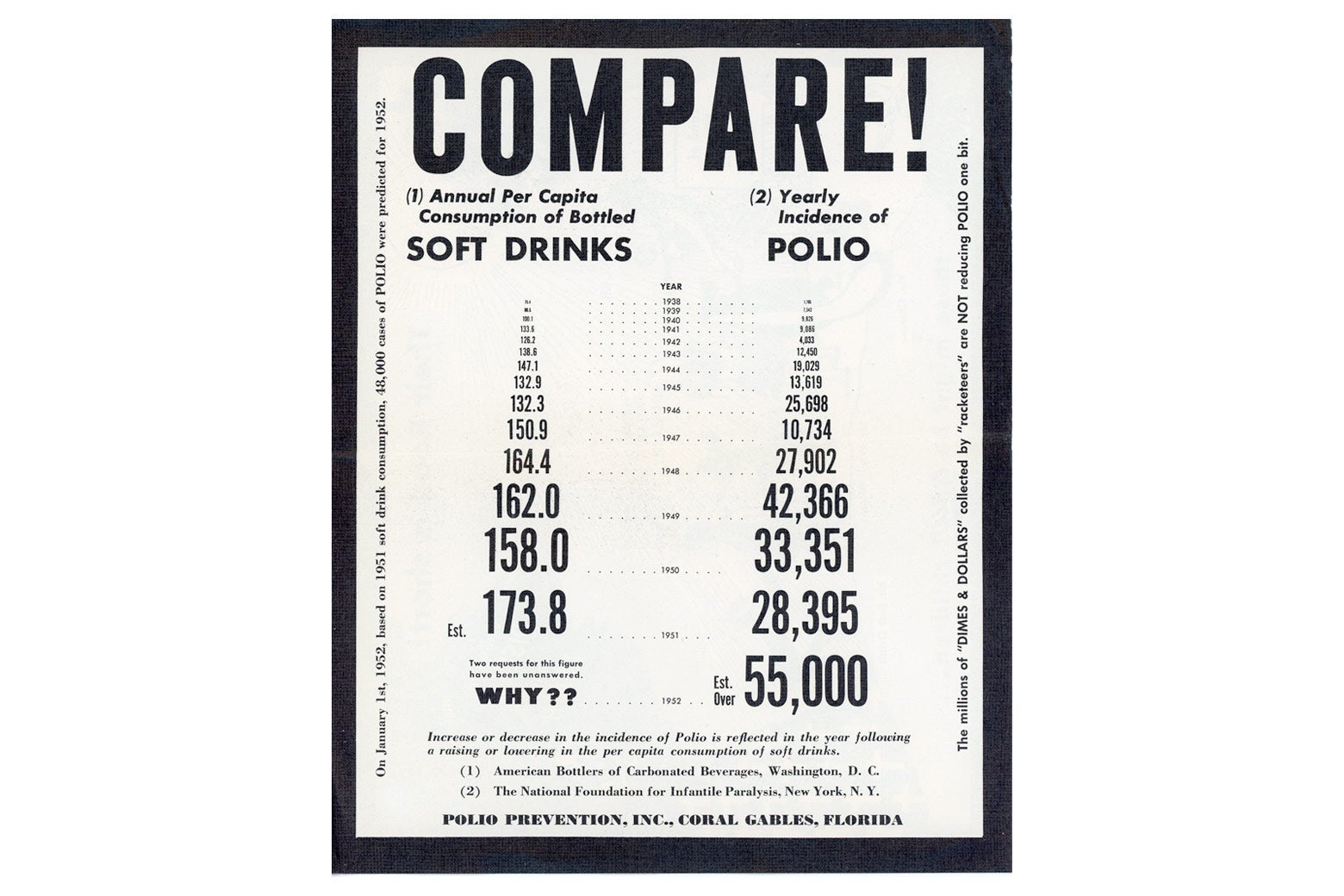

This incident seemed to kindle a volcano in him. Miller drew a correlation between a rise in polio cases—outbreaks were often in the news at the time—and an increase in soft drink consumption. He founded Polio Prevention Inc. and self-published a pamphlet, “Whiskey or Polio.” The only public response was an advisory from the Florida Board of Health that there was no link between soft drinks and poliomyelitis.

Polio vaccine research was funded by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, a nonprofit founded in 1938 by the most famous polio survivor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Riding on public sentimentality for Roosevelt, it was unusually visible for a nonprofit, and pioneered the strategy of focusing on a single disease. A vaccine for polio was the ultimate affront to Miller’s killer Coke theory—and he seemed to bristle at the foundation’s many successful fundraising efforts. He smelled a conspiracy, writing a series of scornful letters to the organization’s president, Basil O’Connor, a former Roosevelt confidant. “I only wish I were in your position … I’D STAMP OUT POLIO … simply by telling the truth and forgetting material profit,” Miller wrote in 1952. “CHILDREN COME BEFORE DOLLARS.”

Two Minnesota counties were early test sites for pre-Salk gamma globulin vaccines, which had a big clinical trial in the early 1950s but were eventually proved ineffective. Because of the enrollment of many local kids in the trials, the area received “quite a bit” of mail from Polio Prevention Inc. in the fall of 1953, according to the St. Cloud city health officer, who asked readers of the St. Cloud Times to discard the organization’s mailers “to guard against uneasiness on the part of area citizens.”

An excerpt: “Sugar is converted to glucose in the body by ONE STEP in the process of digestion … it then goes directly into our blood stream. When sugar ‘steals’ calcium from the blood stream and the pericellular fluid, we get a breakdown in our muscle and nerve cells… disease appears… THIS IS POLIO! A child or adult who is not deficient in blood calcium and whose blood sugar is normal cannot and will not become a victim of POLIO.”

It sounds science-y. It gears readers toward the comfort of a natural and simple solution. (Cut sugar.) And it closes the cognitive loop by discrediting medical authorities who would counter it: “The ONLY possible benefit” of the vaccine, Miller wrote, is “making a permanent cripple to help the advertising wizards of the National Foundation FOR Infantile Paralysis in their bally-hoo for more DIMES and DOLLARS.” He also accused the foundation, the funder and organizer of trials for the Salk vaccine, of having unspecified “cola interests.”

Like today’s COVID skeptics, Miller cherry-picked physicians who were skeptical of polio as a virus and misrepresented facts. One mailer was a rapid fire of out-of-context information: Salk “isn’t entirely satisfied with the vaccine.” Some children still got polio after being vaccinated. And just as the “real” number of COVID-19 deaths pales in comparison to vaccine deaths in some dark corners of the internet, so it was with polio in Miller’s world: “Polio ‘CRIPPLES’ and Polio ‘DEATHS’ are merely ‘Statistics’ to the ‘Charity-Brokers,’ whose record to date of ‘Cripples’ and ‘Deaths’ is TRULY DISGRACEFUL.”

In 2021, Miller might be able to connect with many people who share his beliefs, but in his time he was lonely. Just a few anti-vaxxers rose to any prominence during the launch of the Salk vaccine: Miller; anti–medical establishment crusader Morris A. Beale; and gossip journalist Walter Winchell, who caused a wave of alarm in April of 1954 by announcing on his radio broadcast that “a new polio vaccine claimed to be a polio cure. It may be a killer.” Despite these messages of critique, the polio vaccine largely avoided the mass pushback that dogged the smallpox vaccination campaigns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and today’s COVID-19 vaccination efforts.

“The postwar era was a very trust-in-science era,” said Berman. “There had been [previous] vaccine trials at this time. People were following them. You had a couple of incidents that made people skeptical, but then you saw pictures of Elvis getting the vaccine.”

The smallpox vaccine efforts of the 19th and early 20th centuries occurred, Berman said, when arguments about bodily integrity and religious objection carried as much weight as scientific evidence. Anti-vaccination leagues popped up across the U.K. and U.S., usually to fight vaccine mandates. And COVID-19 anti-vax ideas have spread in an age of online disinformation. But the polio vaccine came when Americans had just seen a rush of scientific and technological advancements, from antibiotics and penicillin to helicopters and television sets. Academics and experts were enlisted to outmaneuver the Soviets. The public not just accepted, but cheered, the headline-making work of guys in white lab coats.

And they were exhausted from years of polio. “The other thing about polio is how visible it was,” said Berman. “It was not out of the ordinary to see children in leg braces or in iron lungs.” The uniquely terrible way polio affected kids—the highly visible cases of paralysis; the deaths; the way it attacked during the summer, when kids were supposed to be running around, having carefree fun—seemed to create parental alarm. “Polio was a disease of children,” said René F. Najera, editor of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia’s History of Vaccines project, “so people were already afraid for their children.” Comparatively, COVID-19 “has largely left children alone … so we don’t mobilize as much.”

As parents prepared to make their kids “polio pioneers,” Duon Miller soldiered on. In the fall of 1953, he handed out Polio Prevention Inc. literature at schools in Key West and concurrently ran an advertisement in the Key West Citizen, declaring that “gamma globulin is absolutely worthless to anyone.” “I’ll crucify those medical men down there,” Miller told the Miami Herald, threatening to send a mailer to “every house in Key West.” In the same interview, Miller said he had spent $12,000 ($122,000 in 2021 dollars) on his campaign. He also contended, in a racist precursor to today’s misinformation claim that COVID vaccines alter one’s DNA, that gamma globulin “can cause Negro, Japanese or other racial characteristics to show up in the second or third generation of persons who take it, if it comes from the blood of such persons of such races.”

Miller wrote letters to the editor to papers across the country, offering to personally be injected with the blood of a polio patient to prove it was not spread by viral transmission. The letters concluded: “What better proof can any man offer?” He placed classifieds reading, “Fake vaccine may kill your child—send a three-stamp for details.”

Gene Rose, Miller’s second ex-wife, told the Dayton Daily News that when she saw him in Coral Gables in 1953, he showed her “a large room at Duon Inc. containing thousands of pamphlets” and “hundreds of dollars in checks, money orders and cash from persons wanting copies of the pamphlets or making contributions.” Mailers contained an offer for 200 reprints for $1. Miller claimed he was shipping bulk orders.

All of his messaging was stamped with the label of Polio Prevention Inc., a name that suggested nonsectarian authority. This is an enduring anti-vaxxer tactic, said Najera. “Very official-sounding group, right?” he said. “It kind of sounds like America’s Frontline Doctors or the National Vaccine Information Center.”

Within months, federal charges ended Miller’s crusade. In March of 1954, as Salk prepared for nationwide trials of his vaccine, prosecutors charged Miller with sending “libelous, scurrilous and defamatory” statements through the mail. The following year, a court sentenced him to pay $1,250 ($12,800 today) in fines and forbade him to send any mail related to medical matters for two years.

Miller proceeded to send material through private “express” carriers, leading to a charge of violating his probation. A year after his trial, he was hauled back before a judge. The judge allowed Miller to skip jail time if he agreed to “have nothing to do with any discussions centering around polio prevention” for the rest of his probation, wrote the Miami Herald.

From the end of his probation until his death, Miller frequently wrote to newspapers, still railing against sugar, “processed bread,” and pasteurized milk. He softened his medical input to lines like “Give us proper diets and we’ll solve the physical imperfections of Americans young and old.” In 1959, the Miami Herald introduced one of his letters with this snarky preamble: “Comes now the periodic letter from Duon H. Miller. … Duon is the wealthy (enough circulate his own voluminous letters) opponent of National Polio Foundation, cola drinks, fluoridation in water, processed foods and just about everything medical men prescribe. He demands an end to these ‘nefarious [fallacies].’ ” That year, U.S. polio cases were about 14 percent of what they were in 1952, thanks to vaccination.