When Kurt Luther walked into Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center in 2013 to attend an exhibition about Pennsylvania during the Civil War, he didn’t expect to be greeted by his great-great-great-uncle. A computer scientist and Civil War enthusiast, Luther had been drawn to researching his own family’s connection to the conflict, gradually piecing together information over years and years. But his searches had always failed to turn up a photograph, and Luther was ready to give up on the possibility of ever seeing his ancestors’ faces. It was only through sheer happenstance that, walking through the History Center that day, Luther had spotted an album of portraits of the men of Company E, 134th Pennsylvania––his great-great-great-uncle’s unit. Laying eyes on his relative’s face for the first time, he later wrote, felt like “closing a gap of 150 years.”

Five years later, Luther launched Civil War Photo Sleuth, a web platform dedicated to closing the gap a little further. Together with Ron Coddington (editor of the magazine Military Images), Paul Quigley (director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies), and a group of student researchers at Virginia Tech, Luther crafted a free and easy-to-use website that applies facial recognition to the multitude of anonymous portraits that survive from the conflict, in the hopes of identifying the sitter. When a user uploads a photograph, the software maps up to 27 distinct “facial landmarks.” Users are further able to refine their searches by adding filters for uniform details that could offer clues about rank. (Three chevrons and a star, for instance, indicates a rank of ordnance sergeant for both the Union and Confederate armies, while shoulder straps with an eagle were worn by Union colonels.) From there, the program cross-references the photo with the other images in CWPS’s growing database. The final search results present an array of possible matches (and possible names) for consideration.

Over the four-year course of the Civil War, photography was a crucial medium for capturing both the shifting tides of the conflict and the individuals caught up within them. Mathew Brady’s searching portraits and Alexander Gardner’s unflinching views of the dead at Antietam helped make the war real for both civilians at the time and those of us at a century and a half’s remove. In an interview with Military Images, Coddington said, “I once calculated that there were 40 million photographs of Union soldiers taken during the Civil War. Even if only 10 percent survive, there are 4 million images out there today.” Yet we have names for few of them: “David Wynn Vaughan, a premier collector of Confederate soldier images, estimates that no more than 10 or 20 percent of the images he’s seen during his more than 25 years of collecting are identified,” Bob Zeller, president of the Center for Civil War Photography, writes on the organization’s website.

The ambitious goal of Civil War Photo Sleuth, Luther says, is to get that number to 100 percent. If it’s a task that seems daunting at the outset, it’s one Luther says will get easier with time. “The beauty of CWPS,” he says, “is that the more people use it, the more information gets added, leading to more identifications—it’s a virtuous cycle.” In the site’s first month alone, CWPS logged 88 reported identifications, of which 75 were “probably or definitely correct” (and since not all users choose to publicize their identifications, Luther thinks that the real number of matches may have been higher). Given that IDs like this are otherwise rare enough that they make national news when they occur, this is a massive leap forward.

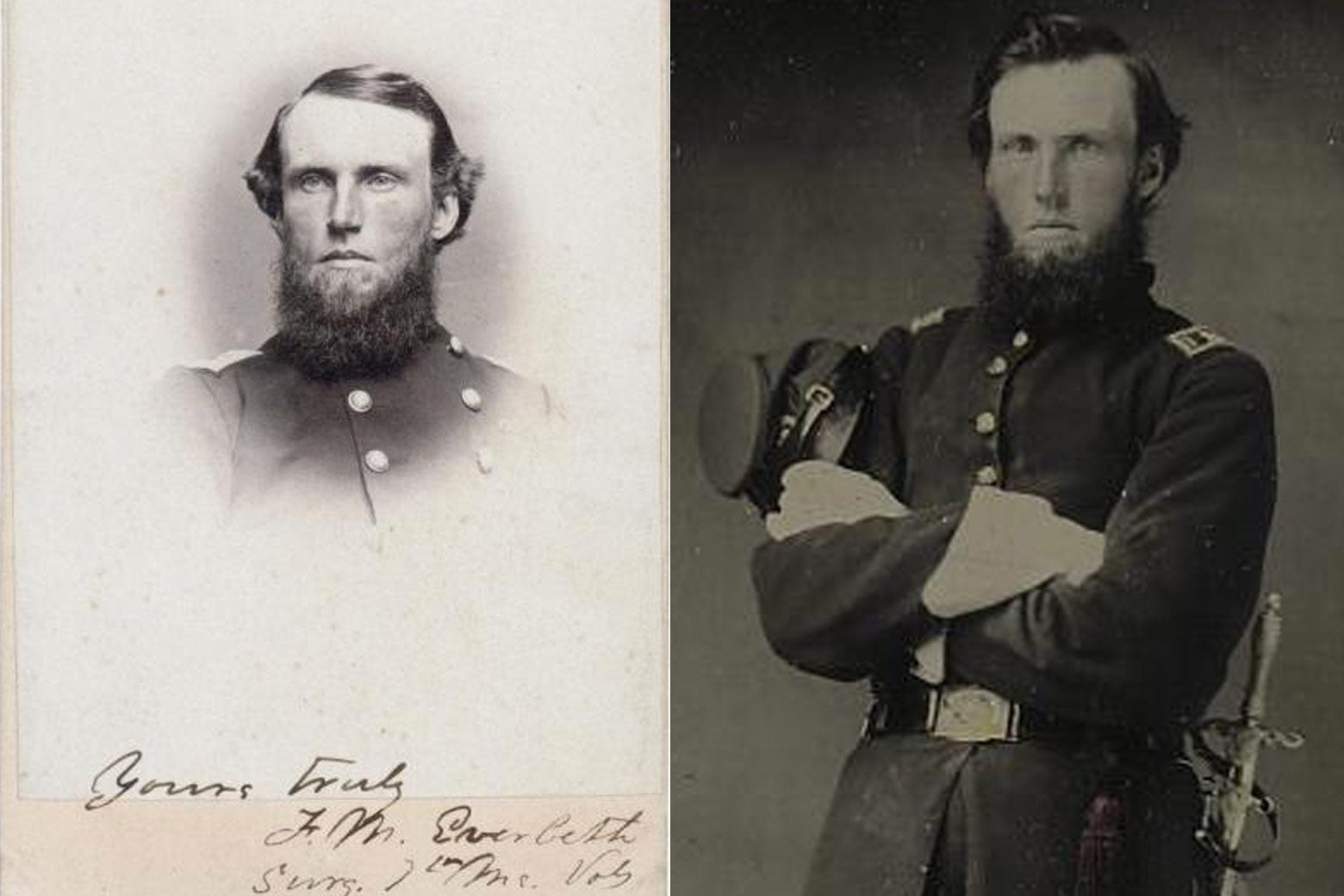

One particularly memorable ID occurred the night before CWPS’s launch in August, as Luther was searching for a sample image for the next day’s demo. After selecting an unidentified portrait from the Library of Congress to demonstrate how to upload and tag photos, Luther ran it through the program. The very first result was a perfect match. More digging turned up yet another portrait of the same sitter, this time with an autograph: Francis Marion Eveleth, assistant surgeon in the 7th Maine Infantry. When Luther presented the match at the launch event the next day, Tom Liljenquist, the man who had donated the photograph to the Library of Congress, was in attendance.

Identifying figures in historic photographs poses a number of challenges. Given that the photography of the time was in black and white or sepia, potentially helpful information about skin tone and eye color is lost. Technological tools developed with modern photos in mind can also run into problems when faced with antiquarian material. Profile views, which were fashionable in the 19th century, are tricky for many facial recognition systems. Similarly, the iconic facial hair sported by many at the time (the word sideburns is an homage to Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside of the Union Army) helps human photo sleuths but hinders software because beards and mustaches can block the features the program is trying to map. While digital tools are extremely useful for drastically narrowing the field, human users still do better when it comes to weighing up several potential matches.

Luther and collaborator Quigley have worked on other applications of digital technology to Civil War history as well. Together with fellow Virginia Tech professor David Hicks, they created a project called Mapping the Fourth of July, which allows users to explore primary sources related to how Independence Day was celebrated while the nation was at war. Nor are they the only historians applying digital tools to glean new insights into material from the period. In January, the Boston Public Library launched a web platform crowdsourcing transcribers for its tens of thousands of abolitionist letters, newspaper articles, handbills, and more.

Identifying photos through programs like CWPS can have a sizable economic impact for collectors. Portraits with names attached almost always command a higher value, benefiting museums and private individuals alike. Beyond monetary factors, of course, knowing who is in a photograph can have a powerful effect on how we perceive the past. As the recent search to identify Sheila Minor Huff––the only black woman amid a sea of white men at a scientific conference in the 1970s––illustrates, projects like this can help recover the presence of those who are frequently overlooked in the historical record. For Luther, part of what motivates him in his work is the human desire to remember and memorialize. “It’s important to give names to these faces,” he says. “Images are powerful, and they humanize these people who might otherwise just seem like names on a list or numbers in a casualty report.”