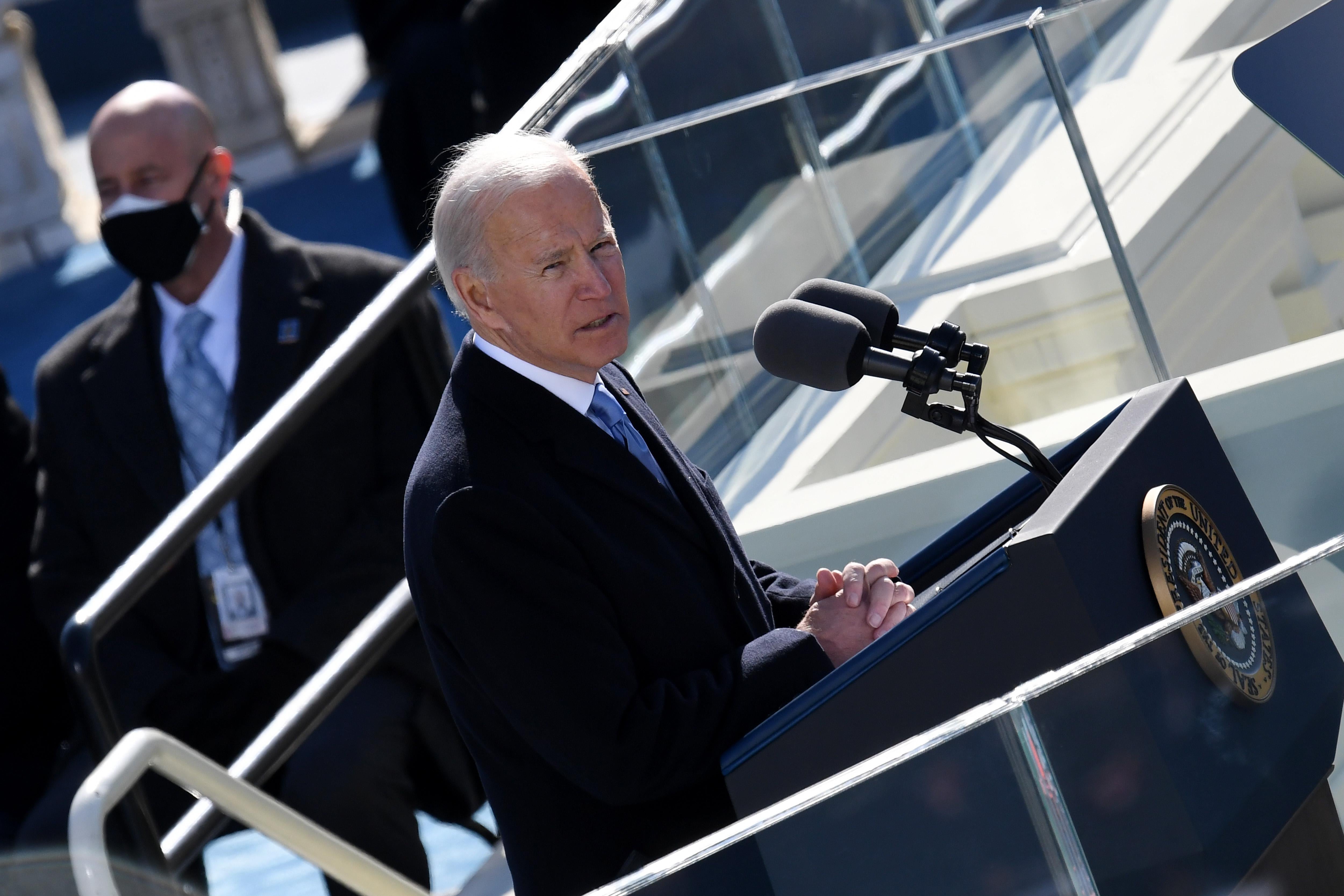

Standing on the west side of the U.S. Capitol, where just two weeks ago a violent mob smashed its way into the halls of Congress to stop lawmakers from certifying his election victory, President Joe Biden used his inaugural address to deliver a moving call for national unity amid crisis, asking Americans to “end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal.“

The speech was in many ways a culmination of the themes Biden campaigned on, given new gravity by the surreal violence of the transition period and by its backdrop: a Washington on military lockdown. As in his remarks accepting the Democratic nomination this summer, Biden talked about the need for common understanding and cooperation, and about restoring the soul of America to a pre-Trump ideal.

But in subtle ways, Biden’s words also revealed a more sophisticated understanding of what “unity” might mean in practice, as well as its limits, than he has expressed before. This was not a speech by a man who expects a great national coming together now that he has evicted his predecessor from the White House, but rather one who is hoping he can convince just enough Americans to bond around common ideals so that the country can survive the conflicts that have, over time, torn us apart.

Early on in his run for the White House, Biden’s promises to bring bipartisanship back to Washington could sound naive, and a bit trite. He reminisced about more cordial days in the Senate, when segregationists and Northerners could still retreat back to their offices to share drinks and strike deals. He assured voters that, once he was president, many Republicans in Congress would experience an “epiphany” and choose to work with him—even though Mitch McConnell’s obstructionism during the Obama administration had offered ample evidence to the contrary. As the long nightmare of 2020 unfolded, with the president tear gassing peaceful protestors and turning basic public health matters into wedge issues, Biden’s calls for peace, love, and understanding began to feel less mawkish, or at least more urgent. But it was never quite clear if he grasped how hard it would be to achieve it.

On Wednesday, Biden’s old overconfidence was gone, his hopefulness cut through with a sense of realism and humility. National unity, he said, was “the most elusive of all things in a democracy.” He admitted that “speaking of unity can sound to some like a foolish fantasy these days,” and far from dismissing the forces dividing the country, he instead called them “deep and real,“ framing them as part of a historic, unending cycle of conflict. “Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal that we’re all created equal and the harsh, ugly reality that racism, nativism, fear, demonization have long torn us apart,“ he said. “The battle is perennial and victory is never assured.“ Recalling Abraham Lincoln’s words from the day he signed the Emancipation Proclamation—“if my name ever goes down into history, it’ll be for this act. And my whole soul is in it”—Biden told the crowd: “On this January day, my whole soul is in this: Bringing America together, uniting our people, uniting our nation.” I’m sure some rolled their eyes at the purple earnestness of it all, but the language showed that, if nothing else, Biden appreciates the scale of the challenge.

It’s useful to compare the president’s rhetoric here with Barack Obama’s first inaugural, when the young president seemed to believe that his election itself represented the victory of hope and consensus over partisan division. “On this day,” Obama said, “we gather because we have chosen hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord. On this day, we come to proclaim an end to the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn-out dogmas that for far too long have strangled our politics.” Suffice to say, petty grievances and worn-out dogmas continued to strangle our politics long into the Obama years and beyond. Biden, in contrast, still sees the work ahead.

Perhaps the most important and telling insight of Biden’s speech was his brief definition of what actually constitutes national unity. “Through civil war, the Great Depression, world war, 9/11, through struggle, sacrifice and setbacks, our better angels have always prevailed,” he said. “In each of these moments, enough of us have come together to carry all of us forward.” The key word here is enough. Biden is not pretending that any politician can bring together the whole country at this moment. He is hoping that a large, sensible majority can stand up to those who’d try to shatter the foundations of our democracy. You can argue with his reading of history (did our better angels really prevail after 9/11?), but it’s an apt description of what unity plausibly means in a nation where political conflict is the historical norm, and it feels especially clear-eyed after seeing so many Republican voters back Donald Trump’s flailing, ultimately disastrous attempts to overturn the election, and demand that their representatives in Congress do the same.

I won’t pretend to know if a national process of reconciliation and healing is really possible at this stage, especially when so much of the Republican party is still controlled by its radical elements. Maybe it’s possible, thanks to the backlash against the Capitol riot, which dropped Trump’s approval ratings down to new lows. But remember that even after the attack, more than half of House Republicans still voted not to certify Biden’s election, showing just how deeply in thrall they are to their antidemocratic elements. It doesn’t help matters that the reforms that might make American politics more stable in the longterm—things like eliminating the filibuster to pass voting rights reform and ban partisan gerrymandering—would require explosive confrontations that Biden and Senate moderates might not have the stomach for. The downside of pursuing unity and bipartisanship now instead of reforming our democracy is that it could set the stage for even deeper, more damaging conflict in the future.

Still, at a moment when the country needs someone to believe we can be better, Biden delivered. At the same time, just because he wants unity doesn’t mean he thinks it will be easy.