There should be two immediate consequences of today’s indictment of 12 Russian intelligence officers for meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. First, Donald Trump can no longer dismiss Robert Mueller’s probe of this meddling as a “witch hunt.” Second, Trump must alter the agenda of his meeting on Monday with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

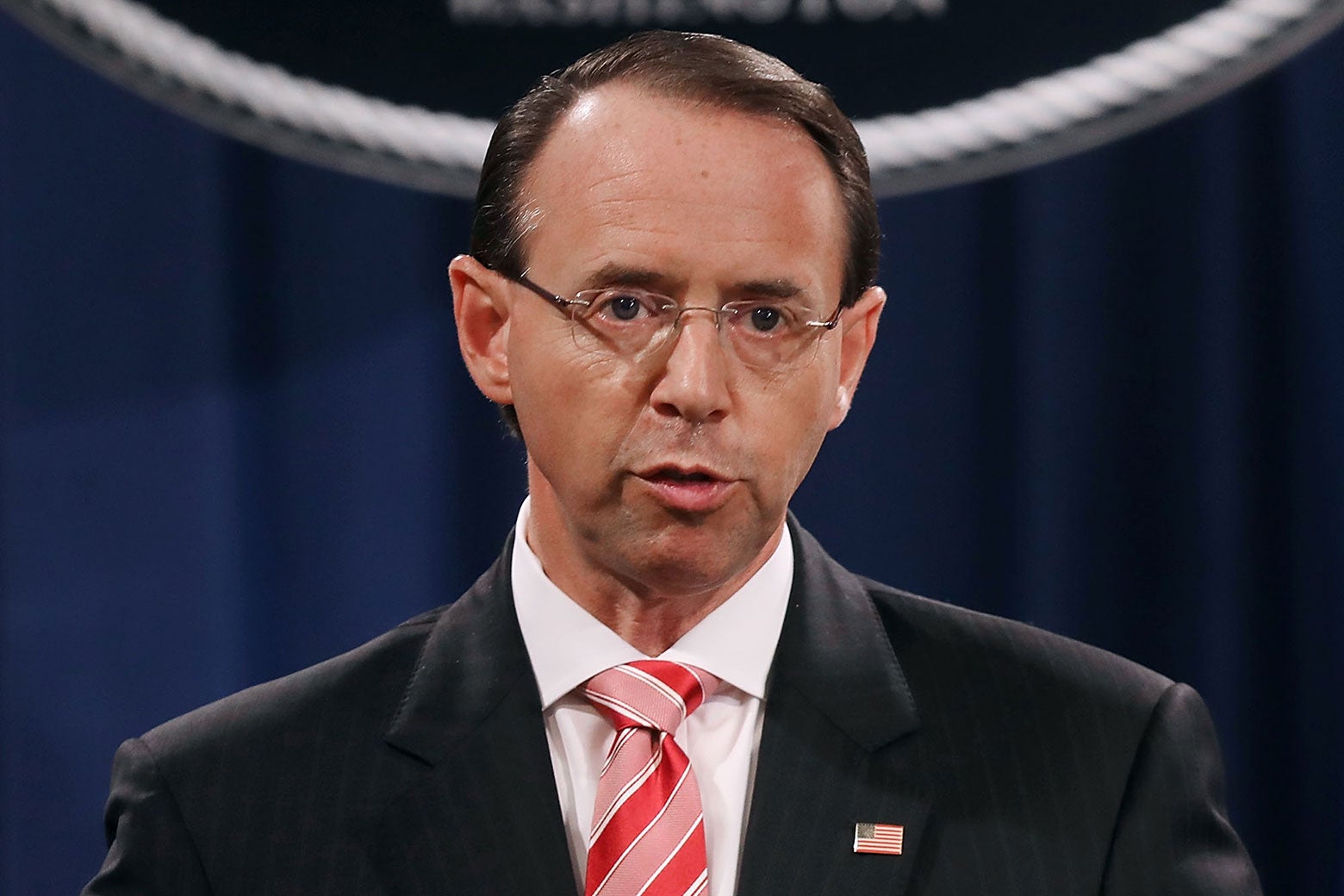

Then again, notice that I said these should be the consequences. Trump has a vast capacity for ignoring inconvenient facts, and he is likely to regard the Justice Department’s 11-count indictment as more “fake news.” Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein said at the press conference announcing the indictment on Friday that he had briefed Trump on the grand jury’s findings earlier this week, and yet, Trump has continued to brush off concerns that he may have won the White House as the result of Moscow’s cyberspycraft.

Trump and his supporters will no doubt highlight one passage from the news conference. The indictment, Rosenstein said, contains “no allegation … that any American citizen committed a crime” or that Russia’s hacking “changed the vote count” or affected the outcome of the 2016 election. One can almost hear Trump and his press aides shrugging off the whole affair, claiming it proves once again that there was “no collusion” on the part of the candidate or his campaign.

However, this would be a willful distortion of the story. It ignores two other statements that Rosenstein made. First, he said, it was “not our responsibility”—not the Justice Department’s mandate, nor within its powers—to conclude whether Russia’s actions actually tilted the result of the election. Second, he added, the goal of Russia’s conspiracy was to “have an impact on the election,” namely to boost Trump’s chances of defeating Hillary Clinton.

In other words, though Rosenstein did not put it this way, the indictment throws further doubt on the legitimacy of Trump’s presidency.

The indictment confirms not only the broad outlines of the intelligence community’s 2017 report but also certain assessments, leaked to the press over the past several months, that had sparked controversy in certain circles. It states, for instance, that key purveyors of stolen emails—notably Guccifer 2.0 and DC Leaks, which claimed to be independent actors—were, in fact, fictitious covers “created and controlled” by the GRU conspirators. It also states that the hacking of several state election boards, and of contractors who verified voter-registration rolls, was also conducted by the GRU.

At his press conference, Rosenstein suggested that this wouldn’t be the final set of indictments on Russian hacking. He said, for instance, that the GRU relied on a private organization to time the release of stolen documents in a way to affect the election. This organization, he noted, is “not identified by name in the indictment,” but it sounds a lot like WikiLeaks, and the reference raises questions of whether its founder, Julian Assange, is under investigation as well.

What happens next? No one expects Moscow to extradite the 12 accused hackers—all officers in the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency. (Similarly, no one expected Beijing to cooperate when the Justice Department indicted five Chinese military hackers in 2014.) However, those officers will very likely now be arrested if they travel to any of the 192 member nations of Interpol.

Meanwhile, how does this affect Trump’s upcoming summit with Putin? It is inconceivable that Putin did not know about the GRU’s election meddling. (The U.S. intelligence community concluded, in its early-2017 report, that Putin directed the effort.) But that may not trouble Trump any more than it has in their previous conversations. At his press conference Friday in England, just hours before the indictment’s release, Trump said he would ask Putin whether he meddled in the election and Putin would likely say “No,” as he has in the past. Beyond that, he said, there’s nothing more to say. (In a June 28 tweet, Trump wrote, “Russia continues to say they had nothing to do with Meddling in our Election!” as if that settled the matter. He then went on to ask why no one was investigating Hillary’s Russia connections or the corruption of “Shady James Comey.”)

With the indictment in the news, just three days before his long-awaited, much-desired meeting with Putin, it might be a stretch even for Trump to leave matters there, much less to push for the “good relations” that he avidly seeks. Proceeding as planned, as if the indictment hadn’t happened, couldn’t help but raise questions—perhaps even among supporters—about his own complicity. Trump could also use the news as an excuse to escalate his war on the Justice Department and to cite the indictment’s timing as evidence of efforts by the “deep state” to thwart his presidency and to embarrass him personally.

If he goes that route, he will be stepping into new realms of internecine conflict. The Justice Department could not possibly return an indictment of this sort—charging 12 individual Russian hackers by name—without close cooperation with several branches of the intelligence community, probably including the National Security Agency, which no doubt at some point hacked the hackers to see who was doing what. (Law enforcement agencies can ask the NSA for technical assistance under closely monitored procedures.)

Rosenstein made one other intriguing remark. “I want to caution you,” he said, “that people who speculate about federal investigations usually don’t know all of the relevant facts. We do not try cases on television or in congressional hearings.” The investigation is taking—or has already taken—directions that no one on the outside knows. Those who still claim it’s a witch hunt or a boondoggle may soon find themselves embarrassed or, in some cases, indicted themselves.