When I heard of Daisy Coleman’s suicide last week, I thought of Antonia Barra, a Chilean woman who died by suicide in 2019, three weeks after she was allegedly raped. Both women are perhaps best known for the causes they came to be symbols for. Daisy Coleman and her friend Paige Parkhurst were raped in 2012, when Coleman was 14 and Parkhurst 13. Both girls watched their community turn on them; they were harassed and threatened for seeking redress while their attackers were celebrated via hashtags like #jordanandmattarefree. The case was outrageous enough that online advocates heard about it and flocked to support them: “Justice for Daisy” became a rallying cry in 2013, just as “Justice for Antonia” has become one in 2020. It is customary to refer to people in Coleman’s position as survivors. I came very close to reflexively calling Barra one as I wrote this. But both women are dead, and so I find myself freshly suspicious of our hashtags and even our most supportive terms.

Coleman was a prominent “survivor.” It matters, then—for how we think about rape—that she didn’t survive. Take the excellent 2016 Netflix documentary Audrie & Daisy, which paired the stories of Coleman and Audrie Pott, who was sexually assaulted at a high school gathering and bullied afterward. Convinced her life was effectively over, 15-year-old Pott took her life days after she was stripped bare, drawn on, photographed, and penetrated by three high school boys. The frame of the Netflix film was—to be blunt about it—that one girl survived and one did not. That doesn’t seem fair now, to either girl.

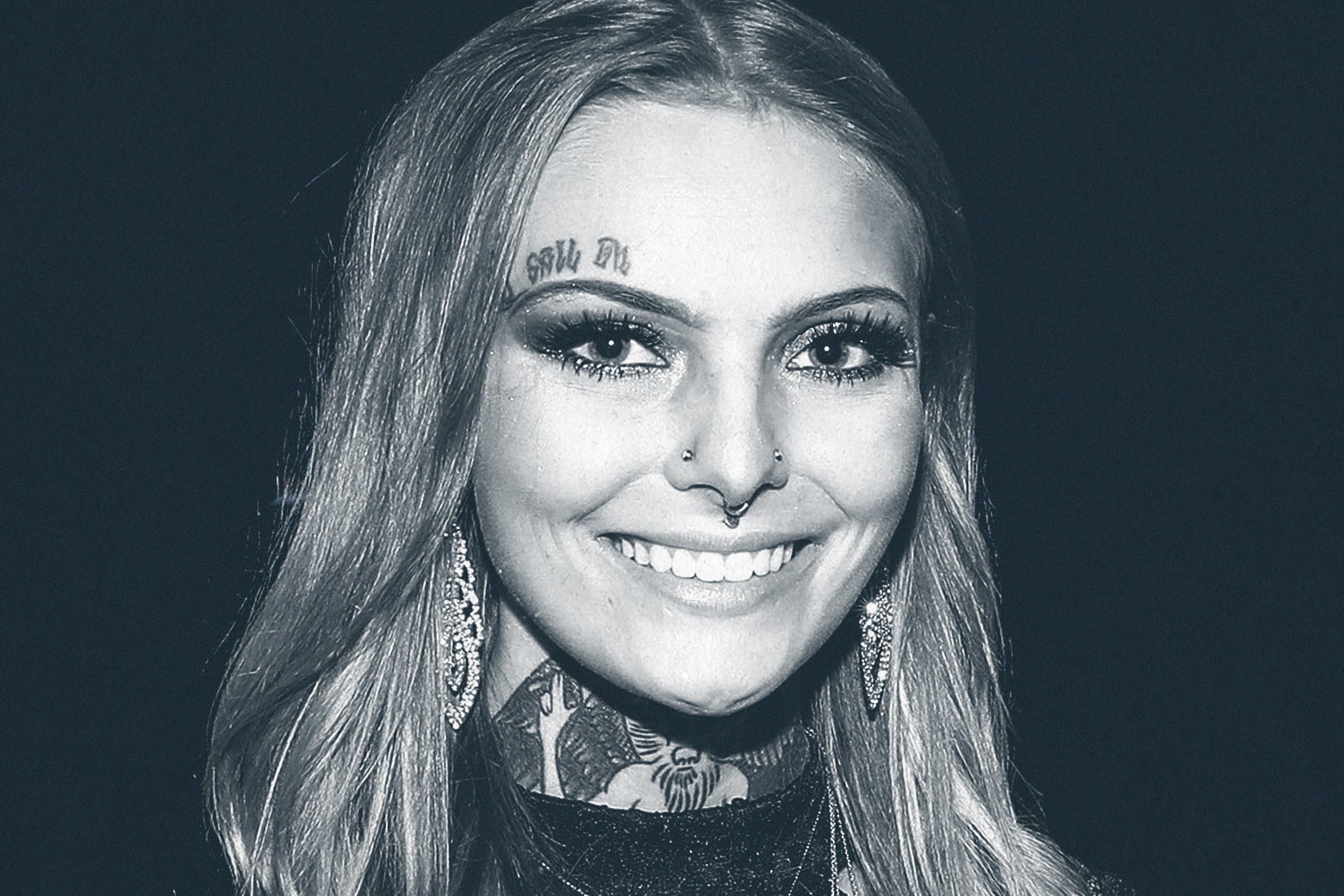

The documentary is well done. It interviews two of Audrie’s tormentors, who appear to have learned nothing at all from the experience despite losing in a civil suit (one of their takeaways is that girls “gossip” whereas boys are easygoing). We hear from Audrie’s parents, who do their best to convey her specificity and uniqueness as a person. Most importantly, of course, we hear from Daisy Coleman. We see her through different phases—always quietly insistent, narrating the epiphanies she’s achieved at enormous personal cost as she looks back on unsuccessful attempts to end her life and forswears suicide in the future. She is an artist; we get to watch her draw. The narrative arc of the film is about mutual rescue: Coleman joins a group of survivors who were assaulted at a similar phase—while in school, disbelieved—and they help one another by dealing with the sense of isolation, the social rejection, and the self-doubt. It’s implied that things might have turned out differently for Audrie Pott if she’d found a similar community. But the burdens of survivorship are real. When Coleman co-founded an organization called SafeBAE for young victims of sexual assault, the narrative load she carried—as someone who was raped and didn’t find justice and went on to become known nationwide—was essential to the program’s mission. The executive director, Shael Norris, told the Washington Post the function she saw Coleman’s story as serving: “I think it was her resilience that has inspired so many other survivors to get help and speak out.”

Coleman was resilient. To be clear, that’s no less true with her suicide. By the age of 23, she had gone through more than many of us can understand. She lost her father as a child and one of her brothers in 2018, both to auto accidents. The documentary can be hard to watch as it reviews the details not just of the assaults but of the aftermath when Coleman’s family became targets in town (their house even gets burned down). It’s hard not just because the events it documents are terrible but because you know that there is more tragedy ahead: her brother’s death and her own. At the time of her death, People reported, she was being stalked and harassed by an acquaintance.

It’s hard to ponder the shortcomings of the “survivor” label, which can potentially flatten someone into a parable instead of a person, without starting to question the other ways we express solidarity and support, even with the best intentions. I felt this acutely when Antonia Barra’s death sparked outrage (and a fresh burst of support for victims of sexual assault) in Chile. Here’s what happened: Barra was allegedly raped in September 2019. She killed herself three weeks later. Other women came forward to say the man Barra accused had assaulted them too, and in late July, that man was finally charged. But the judge permitted him to remain at home under house arrest. The decision provoked outrage (and has since been reversed in an appeal—Martín Pradenas is now in custody). Many people objected to what they saw as a gross but typical miscarriage of justice, and several women came forward with similar experiences. One was a relative of mine. On social media, she described her own sexual assault and said that her rapist was still at large two years later despite her every effort to bring him to justice. She had been instructed not to talk about the case, but she was fed up. She named him.

It was a long and painful account. I scrolled down to the replies, expecting to see the kinds of sympathetic responses one might find in response to such an agonizing disclosure. And there were some. But the bulk of the replies were what I think of as hashtag-based expressions of support, and I briefly went blind with fury when I read them.

“I believe you.”

This is what the replies to her said. Yo te creo. And for the first time I found that boilerplate expression of support—which I know well and haven’t blinked at in other contexts—not just wanting but offensive. I understood, intellectually, that these replies were at the same time perfectly reasonable: Belief is the frame we’ve developed to counteract the skepticism with which sexual assault victims are treated. The intentions are good. But reading the responses, I felt certain that if I came forward with an account of personal harm, I would never forgive—or make the mistake of confiding in—any person who dared say such a thing to me, especially under the aegis of support. Somewhere along the way, it seems we all agreed (I did too!) that the proper response to people who have been assaulted is, in effect, “I do not think you are a liar.” It is reactive rather than responsive. It grants higher standing to the ugly premise that survivors are liars than to the actual pain being expressed.

What brought me to tears, quite unexpectedly, was a spectacle that should have been moving for the best reasons. My relative received a kind and supportive response; this was, by most metrics, the most positive reception a confession of this kind could expect. Why, then, did it feel like so little? Why did victory feel like, well, crumbs? I thought about the time a professor of mine taught Shakespeare’s “The Rape of Lucrece” through a feminist lens—yes, she’d killed herself, but in doing so she reclaimed her own agency. Agency! I was struck dumb at the time by this analysis, and I found myself dumbstruck again as I scrolled through the “I believe you” hashtags. Are we really still in such a blinkered time that saying “I don’t think you’re lying” counts as full-throated allyship? While everyone debates whether Me Too has gone too far, is this really our starting point? Is this where we still are? Is saying “I believe you” really … helpful?

I asked this question of Paige Parkhurst, Daisy Coleman’s friend who was also attacked that fateful night, and who also dealt with rejection and threats from her own community as well as the onslaught of hashtag support that came later. I asked her what it had been like for her to go through all this—and what, if she were in charge, would have actually helped someone in her position. I wondered whether the fact that her rapist at least got a consequence had made a difference. “I was not at all at peace with how our case turned out,” Parkhurst said to me in a DM exchange. “My family attended a court date and there he [pleaded] guilty and was sentenced to spend time in a juvenile detention center. … We found out that he only spent 7 days in the facility and wasn’t on probation for any extended period.”

She also said that being in the national spotlight hadn’t helped. “I have children now and sometimes I worry for our safety. I wonder if the boys or their family will come back, it’s kind of a fear that I think most victims live with.”

Then I asked her about the phrase I’d grown obsessed with. Would it have helped to hear people say “I believe you” back in 2013, when she was on the receiving end of threats and hate? “Yes, I think if the police at least would’ve believed us and listened to us then it would’ve helped tremendously. We looked at them to help us and they failed completely,” she replied. Then I told her about my relative’s social media post and my reaction to the responses. “I do believe that oftentimes we take the bare minimum. I guess it goes to show how much we have failed survivors in our society. I never expected the police to react the way they did. We really put our faith into them and it backfired.”

But is “I believe you” good enough as a standard response? I pressed her. It would have felt good to hear it when the police and the community weren’t listening to her?

“Yes, it would,” she replied.

Maybe these phrases are signposts. They index how bad things have been by offering assurances so basic that in any other context they would sound condescending and even rude. But in a world where disbelief is rampant, they also provide real comfort. I can get as mad as I like about the circumstances that have made “I believe you” a rote response to sexual assault—just as I can agonize over the propriety of a word like survivor when our survivors are taking their own lives. (This is, after all, what survivor is supposed to index—that these are matters of life and death.) But for those who’ve dealt with conditions as they are and not as we would have them be, “I believe you” helps. “I wanted them to believe me,” Daisy Coleman said in Audrie & Daisy. My relative had clicked “like” on every single one of those “I believe yous,” and there were dozens.

If you have been sexually assaulted, you can reach out for help to the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-4673. If you are dealing with suicidal thoughts, you can reach out for help, by phone to the National Suicide Hotline at 1-800-273-8255, or over text message to the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 (on almost all carriers, these texts are free).