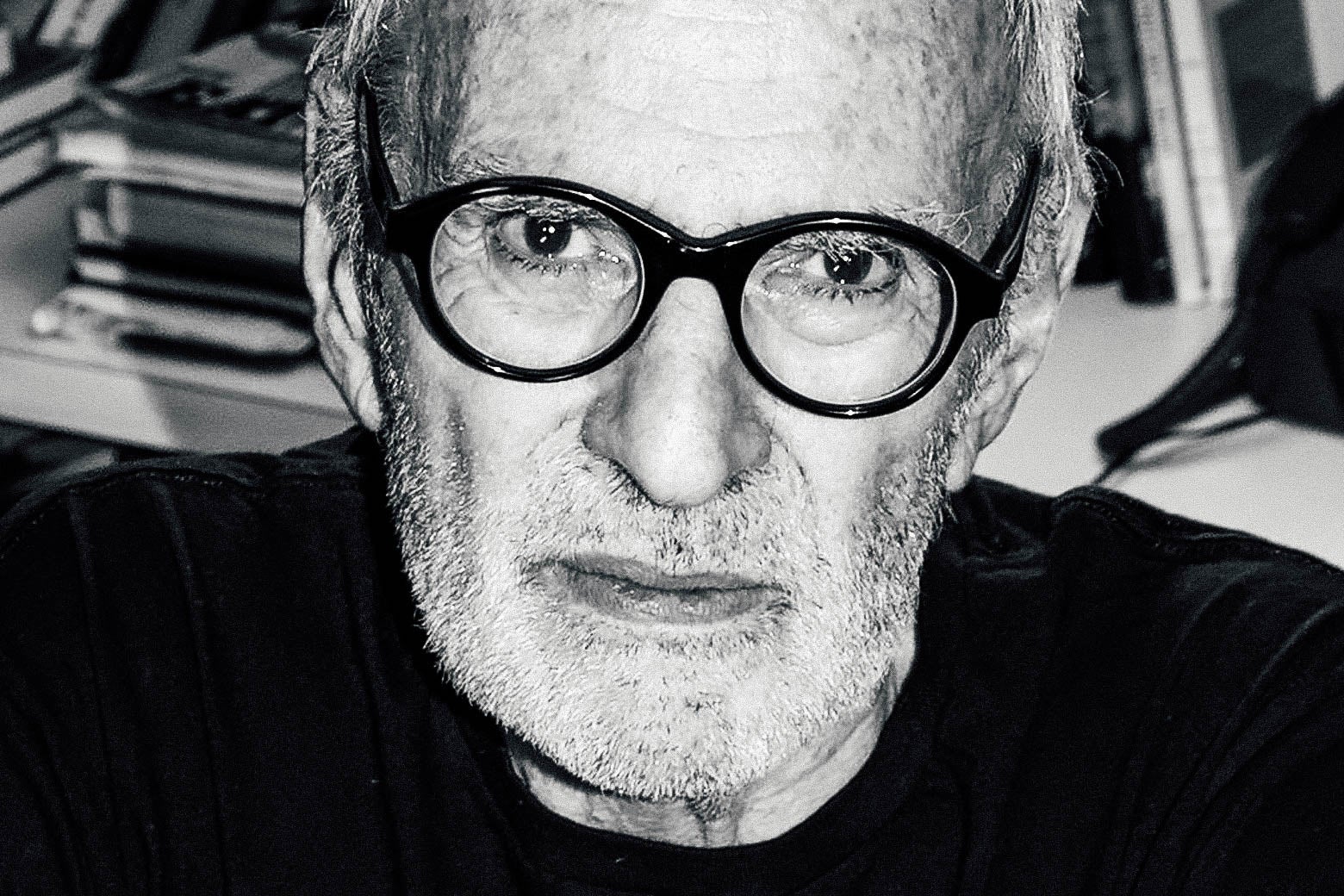

When I think about Larry Kramer, the AIDS activist who died last week at the age of 84, I can hear his voice: loud, urgent, filled with this righteous anger. Larry was tough and uncompromising. But that’s why, as New York magazine writer Mark Harris says, “You can’t make progress without people like Larry Kramer.” Larry’s life was shaped by pandemic and protest—and the way he effected change holds many lessons for today’s movements.

On Thursday’s episode of What Next, I spoke with Harris about the brash nature of Kramer’s activism, the wide-ranging impact he made, and what lessons he would have for today’s activists. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mary Harris: Larry Kramer burned through his life as if he didn’t expect to make it to 84. He was a relentlessly hard worker. As a writer and a satirist, he was nominated for both an Academy Award and a Pulitzer Prize. But AIDS activism was his calling.

Mark Harris: Larry Kramer was an artist and he was an activist. Most times, when you say that about someone, one of those things takes a back seat to the other. We have great artists who also contribute some activism to the world, and we have great activists who were also OK artists. But with Kramer, you’re talking about someone who was really important in both categories. As a novelist, he wrote Faggots, which was a really important step in in gay novels in the 1970s. And of course, The Normal Heart, which is a genuinely activist play and a genuine work of art, an unbelievably tough combination to pull off.

Faggots pissed a lot of people off.

Absolutely. Kramer didn’t write or do anything in the ’70s or ’80s without some gay people saying, “You’re not helping the cause, you’re hurting the cause.” The most famous essay he wrote was a piece called “1,112 and Counting” in the New York Native. It was the first major piece to a very, very loud alarm from a gay man to the gay community about the AIDS epidemic. It infuriated a lot of gay people when it was published.

What about it made people angry?

Everyone was OK with shaking a fist at the Republican government, the Reagan administration, the scientific community, the medical community, all of which were either ignoring this or demonizing people. “1,112 and Counting” was that. But it was also a piece that said we have to wake up: Our community is sleepwalking through this and we’re walking into our own graves. Kramer really took to task people in the gay community who he did not feel were taking the AIDS crisis sufficiently seriously. And he said, we have to change our behavior because it’s killing us.

So he got accused in the most strident terms of being a prude, of being sex-negative, of being someone who hates gay people, of being someone who hates gay sex, of being someone who was mad to be left out of the party and all the fun and who wanted everybody else’s fun destroyed. When you talk about his bravery as an activist, you have to talk about the bravery of being willing to take a stand that will alienate some of the people who should be on your side.

What Kramer ultimately did, over the years, was fight for his seat at the table.

Two years after “1,112 and Counting” was published, Kramer did the first of the two things that perhaps constituted his most lasting legacy as an activist: He co-founded GMHC, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. A couple of years after that, he founded the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, which we now know as ACT UP and which is still around, as is GMHC. ACT UP became an incredibly important protest group, and GMHC, over the years and decades, moved from being a small local grassroots organization to a major national fundraiser and a central point for gay activism.

I think it’s important to remember that anger that ACT UP channeled. I wonder if there’s one scene, one protest that would emphasize that.

The one I’m thinking of was in St. Patrick’s Cathedral and was a very, very famous protest. In 1989, then-Cardinal John O’Connor was giving a mass at St. Patrick’s in New York City and ACT UP disrupted it. They were specifically protesting the fact that O’Connor was fighting against teaching safe sex in public schools and distributing condoms. They lay down in in the church, I mean, St. Patrick’s is big. That was an incredibly important protest because the mainstream reaction to it was This goes too far. I’m sorry for gay people, but how dare they disrupt the Catholic Mass? And there was a portion of the gay community that thought, This hurts our cause. We look like extremists. We don’t have anything to gain by alienating Catholics this way.

I think the one thing Kramer really understood was that not only would an activist movement survive mainstream accusations of bad taste or inappropriateness, but sometimes you had to do that. You literally had lay down your body in an aisle of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. You had to yell at the top Catholic Church official in New York City—“You’re killing us!”—to get people to pay attention.

I want to talk a little bit about Kramer’s relationship with Anthony Fauci, because Fauci worked on AIDS at the National Institutes of Health for years. I feel like their relationship is instructive because it shows how two people can respect each other even if they don’t necessarily agree. And they don’t have to be nice to each other—they can push each other. I found a C-SPAN clip from 1993. Kramer and Fauci are there together talking about a new presidential AIDS task force. And Kramer is so frustrated. He literally says to Fauci that the president is taking Fauci’s balls away. I wonder if you can talk about their relationship and describe it, because it seems so unique but also very powerful.

I think, as we’ve watched Fauci over the past three months, we’ve seen that he is an incredibly patient person who can withstand a lot if he thinks the public health goal is worth it. When you’re talking about the relationship between Kramer and Fauci, you have to give Fauci credit for never walking away from that relationship. He is someone who is willing to be excoriated, willing to be yelled at, and doesn’t stop listening. The lesson of his career is really different than the lesson of Kramer’s. And it’s not a lesson for activists. It’s a lesson for the people whom activists are yelling at and angry at: Don’t prioritize your sense of personal injury or your hurt feelings. Listen to what they’re angry about and see if they have a point and be honest with yourself about whether they’re right. And if they are right, figure out how to work with them.

Fauci kept coming back. He didn’t give up on Kramer, and Kramer did not give up on that fight. He kept that relationship going privately because he knew it was important to him and to the cause. And maybe he also liked Fauci. I think there’s no question that Kramer had respect for him.

I found this other moment of Kramer talking from 1993: He was talking about what change looks like. He’s telling the audience, You have power, your power is your voice. But before that, he says something else about red ribbons: I’m sick of them and I don’t wear them anymore. Instead of wearing a ribbon, he wants people to do something. And it stood out to me because in this moment, I think a lot of people are struggling with what they can do. How can they be allies to the people around them? This week we had this Instagram blackout, with people just posting black squares. I wondered what Kramer would have thought about that.

I would never want to speak for Kramer because I still believe that he has the power to yell at someone for getting it wrong. But I don’t think that Kramer would have been a big fan of the empty gesture or a visual gesture, whether it was a red ribbon or a black Instagram square, that stands in the place of actually doing something. I especially don’t think he would have been a fan of the point of that particular protest this week, which was that everyone should stop talking.

I mean, ACT UP had a theme: Silence equals death.

I’m not disparaging this for people who want to do it. In some ways, it is better than nothing. I think there are probably some people who’d freak out members of their own family by doing that. A meaningless gesture for a corporation can be a meaningful gesture for one particular person. Activism is are not a one-size-fits-all thing. But Kramer was certainly not a big fan of empty gestures.

Kramer had this singular devotion to LGBTQ liberation. But the moment we’re in now is about so much at once: There’s a health crisis and protests against police violence and this economic devastation. I wonder if that complexity makes it hard to replicate what Kramer did.

It’s really hard. I also think it’s important to remember that what Kramer did was not a completely worked out preplanned strategy. It was full of fits and starts. It was full of organizations that he started and then had a bitter rift with. It changed along the way as the world changed, as the plague changed. So if there’s a lesson for today’s activists, it’s probably that have to keep your eye on the long-term goal, but you also have to wake up every day and think, OK, where are we right now? What circumstances have changed since yesterday? How do I need to respond to this moment? I think that is the great challenge for activists right now: to be both farsighted and extremely short-term, to be both idealistic and pragmatic, to think about today and think about the horizon.

And to not get discouraged by mess along the way, because the work is messy.

That’s a great point. Don’t get discouraged by mess. It’s been, to put it very mildly, a messy week and a messy year. And when there is mess, there will always be people who are ready to say, It’s a shame that the whole point of the protest was ruined by blah blah blah. It wasn’t. It isn’t.