In 1976, the historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich published a scholarly article about the representation of women in early American funeral sermons. It was her first published article, and its first paragraph ended with a flourish: “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” Millions of T-shirts, fridge magnets, bumper stickers, and tote bags later, the message is unavoidable: To make history, a woman has to misbehave. To date, the two most successful Kickstarter publishing projects of all time are anthologies of feminist bedtime stories for “rebel girls.” Conceived by a duo of Italian entrepreneurs, Elena Favilli and Francesca Cavallo, Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls Volumes 1 and 2 now retail for $35 apiece, along with posters, greetings cards, and audiobooks. They carry the explicit intention of inspiring young readers to “be more confident” and “set bigger goals,” leaving space at the end of the books for them to draw their own portrait and write their own life story. The million-dollar success of the Rebel Girls enterprise lies in a combination of stylish design, savvy marketing, and the yawning gap in the market for real women’s stories. It’s a gap that conventional publishers have rushed in to fill, but when we cherry-pick the past for icons of female rebellion, are we really serving women, or history?

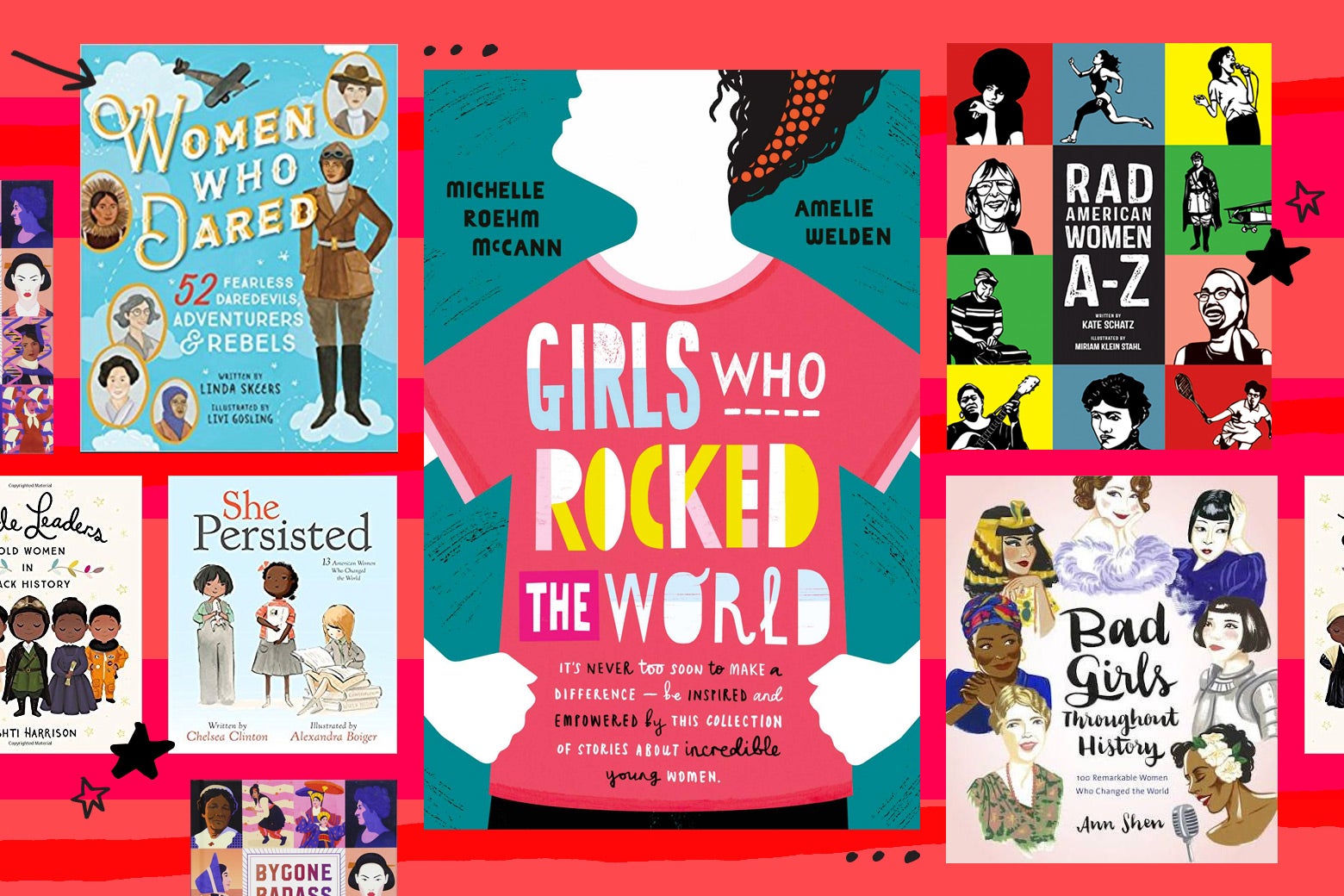

If you’re the parent of a girl between the ages of 4 and 14, you’ve probably watched your daughter unwrap at least one of these anthologies: Women Who Dared, Bygone Badass Broads, Bad Girls Throughout History, Girls Who Rocked the World, Rad American Women A–Z, or Chelsea Clinton’s She Persisted. Vashti Harrison’s Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History and Rachel Ignotofsky’s two collections of “fearless” women in first science and then sports offer a more specialized take. All these lavishly illustrated, lively, uplifting, and scrupulously inclusive anthologies collapse enormous gulfs of time, place, experience, culture, and identity, to assemble women as diverse as the Egyptian queen Hatshepsut, Ada Lovelace, and Serena Williams at the same fantasy dinner party.

There’s no doubt that these books are a valuable corrective to the shelves of histories in which straight white boys grow up to be heroes—as the nonprofit advocacy group We Need Diverse Books has highlighted, it’s vital for children to see themselves reflected in the books they read. But when it comes to helping young people understand their place in history, the shallow kaleidoscope of inspirational biography can’t help but imply that the only women worth remembering are those who stand alone. This narrative obscures the realities of women’s lives, downplays the costs of rebellion, and consigns whole communities to obscurity for lacking the spirit to rebel. This heroic version of history reflects a fundamentally masculine narrative of genius and exceptionalism that is the root cause of women’s underrepresentation in history books in the first place.

The women celebrated in these books as heroines are often firsts, those who have managed to break through into some professional or political arena previously dominated by men. There are plenty of leaders, singular and isolated by the nature of their position, who are celebrated for the fact of their power, not for the ways they might have wielded it: Margaret Thatcher, Elizabeth I, Indira Gandhi, Catherine the Great, Aung San Suu Kyi. Others are quasi-mythical figures, whose lives are so obscured by legend that the truth is hazy: Boudicca, Joan of Arc, Nefertiti, Sybil Ludington, Mata Hari. They sit rather incongruously alongside contemporary celebrities, from Oprah to Simone Biles, whose lives have been widely documented and whose long-term legacies remain to be determined.

It is hard to know what message young women are supposed to take about the grouping of so many wildly different women under the label of “rebel” or “badass,” beyond the comforting idea that women’s progress moves in one direction, from exclusion to equality, and that barrier-breaking is an end in itself. Just last month, conservatives complained that Gina Haspel was not being duly celebrated by feminists for becoming the first woman to direct the CIA, as if breaking the tape were more important than any human-rights violations committed on the way. (Torture: very badass.) For the most part, these books participate in a myth of history, especially children’s history, as apolitical, inoculated by time from the arguments of the present.

Too often, the histories of women are split between the overfamiliar and the overlooked. In her 2013 biography of Rosa Parks, historian Jeanne Theoharis describes how a reductive hagiography came to overwrite her subject’s life of dedicated activism with a single, simple story: nice older lady, tired of both racism and subpar public transportation, makes a morally unambiguous protest. Parks made history precisely because she was well-behaved, because her image was so wholesome and unthreatening, and her protest stood out as an apparently isolated act of forgivable “misbehavior” in an otherwise virtuous life. She was a much safer heroine than working-class teenager Claudette Colvin, pregnant out of wedlock, who had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus several months earlier. (A tip of the hat to Chelsea Clinton, the only anthologist who includes Colvin.) This was the story President George W. Bush told when he signed the bill to make Parks the first black woman honored with a statue in the U.S. Capitol, shortly before his Supreme Court nominee Samuel Alito would be confirmed. On the day in February 2013 that Parks’ statue was unveiled, Alito sided firmly with the court’s conservative majority to gut the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a cause for which Parks worked for most of her life.

When the corrective to women’s exclusion from history is to find a few suitable individuals to pluck out of the messy rush of life and achievement, and hold up for admiration, we forget that many of women’s most important historical achievements—Parks’ included—have been the product of collaboration, community, and collective action. Making change, especially in the lives of women and marginalized people, doesn’t happen in isolation. There’s a particular irony in the fact that the label “rebel girl” has its own history in early-20th-century labor activism. It was applied to, and embraced by, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a working-class Irish girl from New Hampshire who was making speeches for the Industrial Workers of the World by the age of 15 and celebrated in song by labor activist Joe Hill. None of these books feature the original rebel girl, although Chelsea Clinton’s She Persisted, perhaps surprisingly, celebrates Flynn’s contemporary Clara Lemlich, a leader of the massive 1909 garment industry strike in New York. Revolutionary labor organizer Lucy Parsons is the L in Kate Schatz’s Rad American Women A–Z, which is dedicated more explicitly than the other anthologies to politically active women, and Dolores Huerta appears in more than one collection. But elsewhere, women who organized on behalf of their fellow workers, or who made change collectively, are relatively scarce.

In 2007, Ulrich wrote a book revisiting her accidental feminist slogan, explaining the roots and resonance of her phrase, and the slippery notion of behavior, good or bad. As Ulrich is well-aware, the catchy slogan is misleading out of context—her actual essay subjects were the well-behaved women remembered, not forgotten, in those pious sermons. But Ulrich’s real point is not that we need to change how women behave, but instead, how we “make” history. According to a 2016 Slate survey, fully 75 percent of more than 600 trade history books on the previous year’s New York Times best-seller list had male authors. Biography subjects, meanwhile, were more than 70 percent male. But done right, women’s history offers more than a corrective to the heroic narratives that men have written for generations. Annette Gordon-Reed’s work on Sally Hemings made it impossible to keep telling the same story about Thomas Jefferson. Hemings, of course, did not have the freedom to be a rebel—her good behavior, within the inhuman constraints of her life, allowed her to survive. But in Gordon-Reed’s hands, her story, and her presence in history, proved transformative. Done right, women’s history changes history.