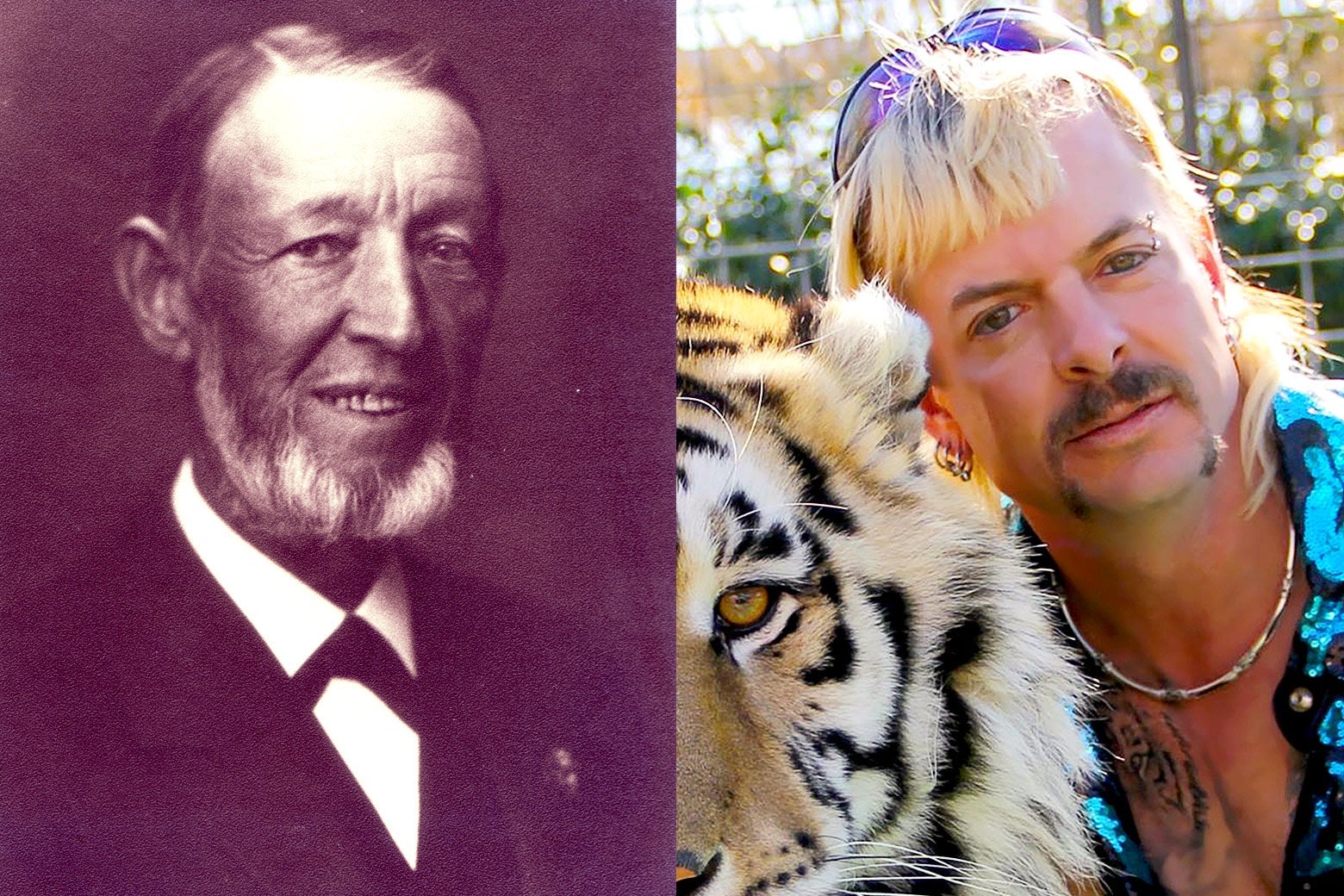

Netflix’s hit docuseries Tiger King is so relentlessly crazy that it’s easy to think that its particular breed of bananas sprang from the present moment fully formed, like a leopard-clad Athena leaping from Zeus’ own blond mullet. But the show, which, for the few who have not binged it, focuses on a flamboyant tiger breeder and zoo owner who calls himself Joe Exotic, is evidence of a long Western tradition of exotic animal entertainment, and of a commoditized attitude toward animals that goes back to the 19th-century genesis of private zoos and menageries.

Exotic animals have been part of Western culture for hundreds of years, at first generally as part of private collections meant to demonstrate the owner’s status and ability (not unlike, say, Mike Tyson owning a tiger). But where in previous centuries there were an isolated few animals in private hands, to amuse their owners or appear as portrait accessories, during the 1800s the menagerie emerged as a fundamentally public entertainment. In that era, museums and zoos had not yet become the starchy public scientific institutions we now think of. Most early venues were private functions existing at the whim (and budget) of a single proprietor, and in order to get visitors in the door, budding American entertainers of all stripes readily turned to animal performers. “Nothing,” confirmed a New York Times reviewer in 1862, “creates so great an interest as a zoological collection.”

These early, hungry entrepreneurs relied on a blend of novelty and charisma that Tiger King’s viewers will certainly recognize. The Van Amburgh menagerie performed in New York in 1862 with a show that featured lions, tigers, and “performing ponies who fire off pistols.” In the 1890s, the Siegel-Cooper department store housed a live elephant for a month until a local zoo bought it for $2,000. Is the story somehow incomplete without a good fringed leather jacket? You can have that, too: John C. “Grizzly” Adams arrived in New York City in 1860, wearing a hunter’s suit of fringed leather festooned with the “hanging tails of small Rocky Mountain animals,” and performed for visitors under a canvas tent in Lower Manhattan with nearly 30 grizzly bears, one of whom wore a bonnet and glasses. The entertainment icon P.T. Barnum certainly had Joe Exotic’s sense of flair—running for (and actually winning) a seat in the state Legislature, playing feuds and humbugs for maximum daily press, and keeping a huge menagerie in his American Museum, including beluga whales, for whom water was piped in from the nearby East River.

Perhaps the biggest figure in 19th-century animal entertainment, though, and the most relevant to the modern subculture we see in Tiger King, was the German animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck. The Hagenbeck family business began with Carl’s father, a fishmonger who would buy any unusual animals that happened to come off the Elbe river docks in Hamburg—seals, raccoons, or monkeys—and show them off for additional income. Not content to simply display or resell animals already on the European continent, young Carl began to build relationships and a supply chain to bring in exotic animals from Africa for circuses and menageries, and solidified his reputation with one 1870 shipment to Europe that included a rhinoceros, four buffaloes, five elephants, 14 giraffes, 30 hyenas, more than a dozen big cats, 26 ostriches, 20 crates of monkeys and birds, and 72 goats to supply the animals with milk and meat.

This was not a gentle process, and the international animal trade was its own form of colonialism. Since the potential for profit was so enormous, Hagenbeck paid agents and local hunters in Africa and Asia a pittance to secure as many animals as they could, with little regard for method or brutality. Animal dealers generally preferred to capture young animals, as they were more manageable and had better odds of living through arduous journeys over land and sea. This meant hunters usually separated parents from their young, chasing adult animals away or simply slaughtering them. “These great creatures,” wrote Hagenbeck, “turn vigorously to defend their young; and the latter cannot as a rule be secured without first killing the old ones.” Nonetheless, despite the large number of captures and the supply of goats, “even with this precaution a large number of the captives die soon after they have been made prisoners, and scarcely half of them arrive safely in Europe.” Even at a 50 percent death rate, the trade was profitable.

Audience members had no particular reason at this time to suspect that there was any special complicity or shame in animal entertainment, animals then being mostly regarded as unfeeling subjects of human dominion. Hagenbeck had good reason to keep up a steady flow of remarkable young animals: People paid handsomely to see them, over and over again. (He would, to be fair, do nearly anything if it promised a profit. When revenue dipped a bit in the 1870s, Hagenbeck asked his staff to bring a family of the “least civilized” Laplanders along with the reindeer they were importing, and to thereby exhibit them as an ethnological curiosity.)

Since international trips were grueling and risky, even at a profit, breeding became an attractive concept with an even more attractive benefit: adorable cubs. Hagenbeck bred lions, tigers, snow leopards, and hybrid animals, claiming that it was “not very difficult to carry out experiments in cross-breeding. I have bred many young from lions and tigers.” Hagenbeck set precedent for today’s private zoos, reassuring readers of his autobiography that keeping a tiger, say, in a pack-and-play in the den, was not only feasible but a very normal sort of entitlement: “All carnivores without exception, when they are caught young and are properly treated, are capable of being brought up as domestic pets.”

But as time went on, public opinion began to sour on the animal trade, and the animal rights movement came into broader prominence through activism and laws like the 1900 Lacey Act (the Big Cat Public Safety Act, discussed in Tiger King, looks to build on this law). Faced with challenges to image and profitability, animal venues had to find a sense of place in the world, and replaced brutal dominion with moral purpose—the idea that audience members paid to participate in education, science, and conservation. Once it became a liability to show how the sausage was made, Hagenbeck and contemporaries quickly rebranded themselves as kindly benefactors, creating spaces where their charges were safe from humans and cruel Nature. Proclaiming a commitment to positive training methods and nonintervention by humans, in 1907 Hagenbeck established an open-air animal park in Germany (you could, though, still get an ostrich-cart ride or eat at the restaurant; no comment on the food).

Carl Hagenbeck was happy to throw a wrap of conservation ethics over his ugly past to keep his career going strong. Tiger King’s various subjects likewise claim that their businesses— however weird, or cultish, or accompanied by baffling country ballads they may be—are all about a love of rare animals, and while the documentary doesn’t shy from presenting any of the associated mayhem, it also doesn’t challenge that motivational statement. When conservation is a convenient add-on meant to distract and appease a paying audience, we can’t pretend that private zoo owners like Joe Exotic or Carl Hagenbeck have been drawn into their business by anything but their own mythmaking.