In a press release on Monday, the Department of Housing and Urban Development made its firmest commitment yet to tear down the Obama-era framework for enforcing the Fair Housing Act.

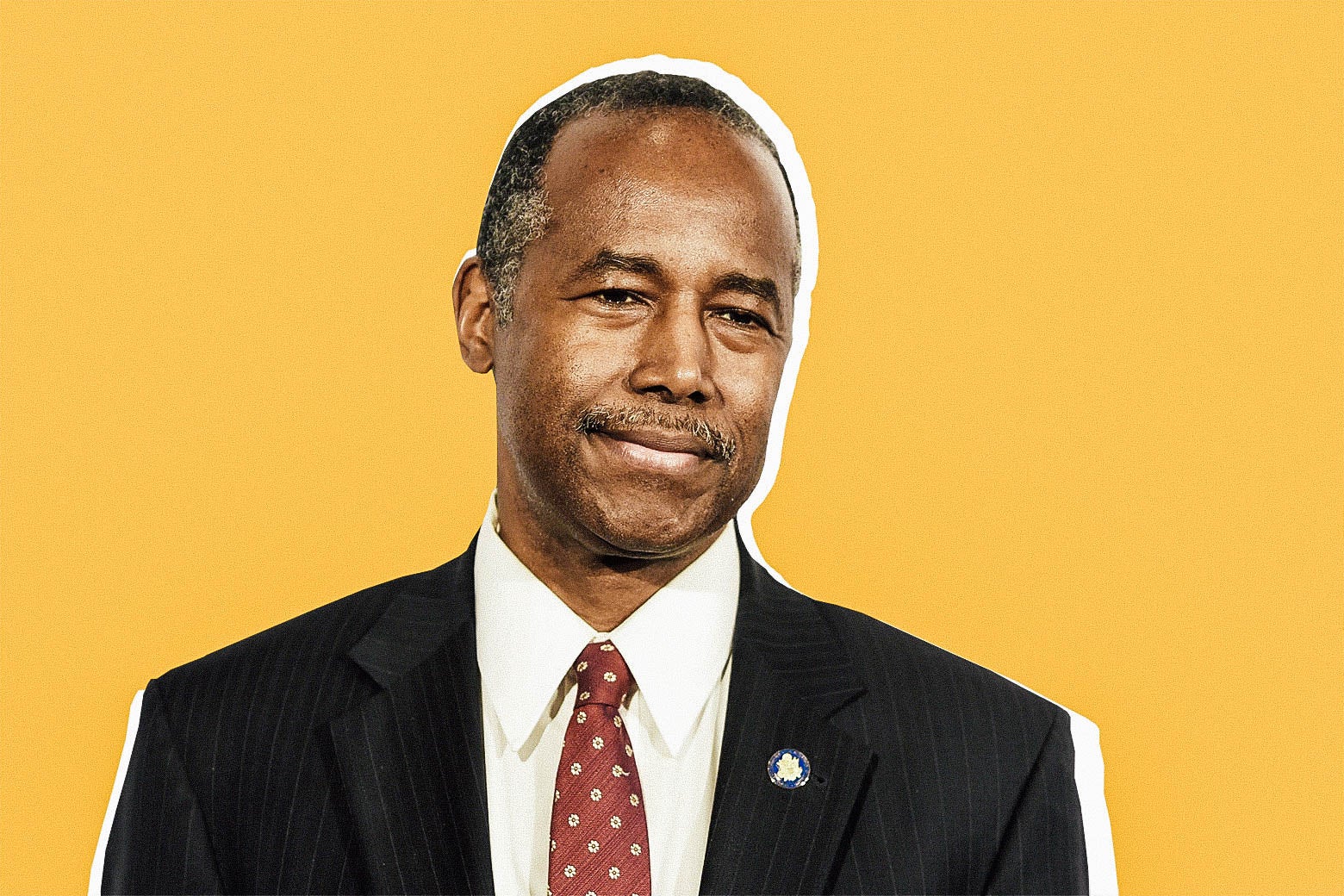

In a public notice dated Thursday, Aug. 9, HUD outlined its reasons for quashing the 2015 “affirmatively furthering fair housing” rule (AFFH), which had been the strongest effort in decades to crack down on segregation and discriminatory practices in and by American cities and suburbs. HUD Secretary Ben Carson cited the Obama administration’s “unworkable requirements” in a statement, saying the rule “actually impeded the development and rehabilitation of affordable housing.” Under AFFH, Carson said, cities and other HUD grantees had “inadequate autonomy” according to his understanding of federalism.

Neither criticism, fair housing experts say, is accurate. The AFFH rule told cities to set fair housing goals, but not how to meet them. It was flexible on doctrinaire questions like: Should assistance go to people or places?

Neither did the rule seem likely to dampen the supply of affordable housing. “It’s important and worthwhile and corresponded to the importance of what it’s designed to do,” says Andrea Ponsor, the COO of Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future, which advocates for the preservation and production of affordable rental housing. “We were very supportive of the rule and we don’t feel like it had its opportunity to work yet.”

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal published on Monday, Carson framed the change as a way to bolster housing production across the board. “I want to encourage the development of mixed-income multifamily dwellings all over the place,” he told the paper. While it’s true that the affordability crisis is in part rooted in housing starts per capita hitting a 60-year low, the Fair Housing Act is intended to attack segregation, not scarcity.

That comment does not mesh with Carson’s established philosophy. In his only published commentary on housing policy before his appointment to HUD, he called the 2015 AFFH rule “social engineering” that would “fundamentally change the nature of some communities from primarily single-family to largely apartment-based areas.” Fair housing advocates would have found that a dreamy, if outlandish scenario. Recipients of Community Development Block Grants have been required for decades to “affirmatively further fair housing,” but have rarely if ever been punished by HUD for not doing so.

A quick glance at the notice reveals that while the secretary contradicts himself, the outlines of a policy—to the extent they can be read that way—hew closely to conservative orthodoxy on housing, which is to reject federal efforts to demolish the walls that wealthy white suburbs have built. HUD’s new approach does not appear likely to increase production or decrease segregation. Instead, it poses a series of questions that appear almost painfully rudimentary on the heels of the Obama administration’s six-year effort to draft the AFFH rule (and 50 years of rampant local disregard for the FHA), such as:

• “Instead of a data-centric approach, should jurisdictions be permitted to rely upon their own experiences?”

• “How much deference should jurisdictions be provided in establishing objectives to address obstacles to identified fair housing goals, and associated metrics and milestones for measuring progress?”

One of HUD’s new goals is to “provide for greater local control,” a phrase understood to conjure the strict, racially-motivated land use laws that were developed by American suburbs to keep out minority populations.

In January, HUD told jurisdictions to abandon the Obama protocol and return to a previous self-evaluation called “analysis of impediments,” or AI. Those analyses were cursory and devoid of specific goals, the Government Accountability Office concluded in a 2010 report that led HUD to develop the new AFFH rule. After HUD reverted to the toothless old standard from AFFH in January, New York state sued, alleging the suspension of the rule would increase segregation and make it harder for cities to comply with the FHA.

Supporters said that jurisdictions that participated in AFFH had committed to concrete reforms. Under AFFH, Chester County, Pennsylvania, a cluster of wealthy Philadelphia suburbs, committed to decreasing the number of Section 8 recipients living in high-poverty tracts from 44 to 39 percent, and outlined how that would be accomplished.

While the shift announced Monday says little about Carson’s plans for enforcing the Fair Housing Act, it does outline some specific criticisms of the 2015 rule.

One is philosophical: The AFFH goals just didn’t make sense. Citing a 2016 study of the landmark “Moving to Opportunity” project, which helped get low-income families out of high-poverty neighborhoods, Carson’s HUD argues that the benefits of deconcentrating poverty “are likely limited to certain age and demographic groups and difficult to implement at scale without disrupting local decision making [sic].”

Lawrence Katz, a professor of economics at Harvard and one of the cited study’s co-authors, disagreed with that assessment. “I have a quite different interpretation of the findings from our 2016 MTO study,” he wrote to me in an email. “Overall, the research shows that deconcentrating poverty is likely to greatly improve the health and well-being of low-income families and to have long-run economic and educational benefits for the children of low-income families.”

The other critique was practical: The AFFH was simply too much trouble. Jurisdictions were required to use one of HUD’s “assessment tools” to analyze their performance on various fair housing metrics. The rollout of those tools—part of which occurred under Carson’s watch—did not go smoothly, and affordable housing advocates had warned HUD that making the tools too complicated would strain or delay local government responses. As evidence that the Local Government Assessment Tool was “unworkable,” Carson’s HUD noted that 31 of the 49 assessments submitted before January 2018 were initially rejected.

That, argues Nicholas Kelly, a Ph.D. candidate at MIT who conducted the first systematic evaluation of the AFFH plans, is exactly the point. One object of the AFFH rule was to ensure that HUD no longer functioned as a meaningless rubber-stamp for local officials that didn’t take housing choice seriously.

“We have not found the process was very burdensome,” Kelly said of the review of the 49 plans, which was conducted with MIT’s Justin Steil. “Those that were rejected had a back and forth, and HUD was very helpful. We found the rejection process was actually focused on achieving positive results [another Carson criticism of AFFH]… a dramatic improvement.”

The MIT team also called all the cities who had been set to submit AFFH plans for the most recent cycle, before Carson killed the rule in January: “We found cities were very bewildered. Right as they were about to submit, HUD pulled the rug out from under them. To their credit, many submitted their AFFH plans anyway, under the AI frame.”

In the future, jurisdictions working with HUD won’t have the option of using the more demanding results-oriented “Local Government Assessment Tool” developed for the AFFH rule: Carson’s HUD took it offline in May.