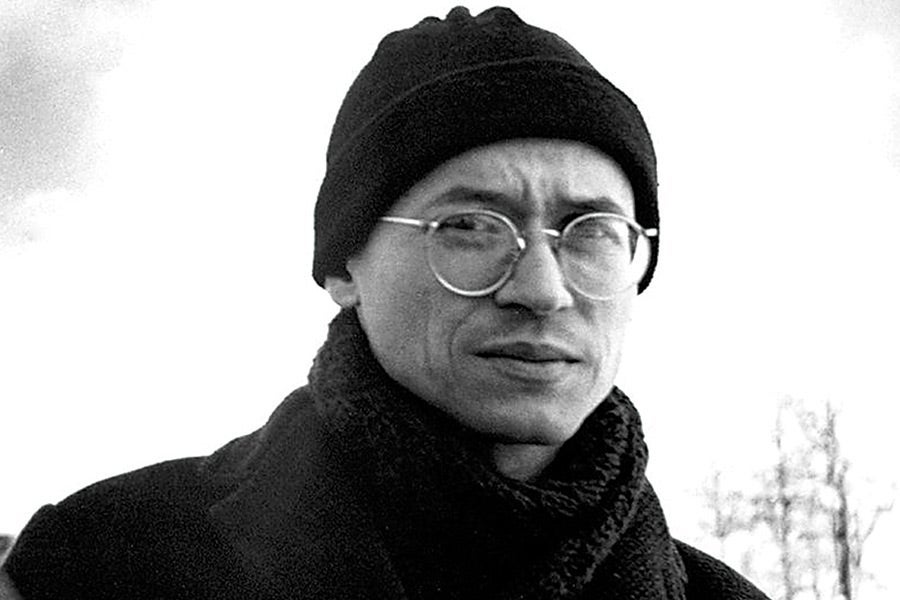

On this week’s episode of Working, Isaac Butler spoke with comics journalist Joe Sacco about his new book, Paying the Land, which explores an Indigenous Canadian community’s relationship to the changing environment. They discussed Sacco’s unique approach to covering some of the world’s thorniest issues, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Bosnian war, and what it means to balance the facts of journalism with the subjectivity of illustration. This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Isaac Butler: Many of your book-length projects take a very long time. You spent four years making Paying the Land, and Footnotes in Gaza was even longer than that. Is there a moment when you’re chasing a story where it just clicks? How do you figure out that you’ve found a story that is worth investing that much of your life in?

Joe Sacco: It has to hit me in the gut. I have to feel something inside me that’s telling me that this is going to be worth several years of work. It has to be something that really pulls me in, because it’s a difficult process. There’s always this feeling—I won’t say it’s a moment, but it’s a cumulative feeling until I realize, “This is really worth the effort.” In this particular case with Paying the Land, it was doing a 60-page story for a French magazine about the subject and realizing I hadn’t done as good a job as I thought I could do. A lot of doors were beginning to open up, and I needed to make another trip back and go deeper, because it was quite a complex story. It was feeling that the story was owed something more.

Do I want to spend years of my time doing it? If the answer is yes, you just go ahead. You always have a midproject crisis. About two years or three years into it, I’m always almost overwhelmed. You get older and you realize, “Oh boy, I’ve still got two more years to go.” Finances get a bit tight. The advance runs out a lot quicker than you would hope it would. But you always listen to who you were when you made that decision. You always say, “That younger me decided to do this, and I’m going to listen to whoever that was back there,” and you keep going. That gets you over this hump, and then it’s OK.

In all of your books, people are telling you some really heavy shit. They’re talking about very, very painful things. Sometimes it’s inherited traumas, or griefs that go back generations that they’ve been living with their whole lives. In Paying the Land, there’s the experience of children being ripped away from their parents and sent to residential schools. There’s drug and alcohol abuse. There’s physical and sexual abuse. There’s deep rifts within communities. How do you go about making sure that subjects know they can trust you with what they’re giving you?

Often that starts with who your guide is. In this case, Shauna Morgan. She’s Euro-Western, not Indigenous, but she’d worked a lot in the communities. There were people who trusted her, and she introduced me to them. That was an advantage. That’s true in places like Gaza. I always looked for someone who wasn’t necessarily a professional translator but who could speak English well enough. The main thing for me was always: Was this person trusted in the community? What was the person’s standing in the community? Was their family well respected? And if my guide was trusted and had paid his own dues in the community and he was introducing me around, that reflected on me.

The other thing is learning to listen, which is something I’ve learned over time. In the case of Paying the Land, I had to listen in a different way, because I was told when people start speaking, the culture is you let them speak, especially elders. Elders have to be respected in many ways, and one of those ways is you ask a question and let them unwind the story in the way they want to, or explain something in the way they want to explain it. That was unusual for me, because I’ve gone through some of my old interviews and I realize how many times I cut people off before they got to something really interesting, because sometimes I wanted to demonstrate my knowledge of the subject. Over time I’ve learned to keep my mouth shut better.

Your books are so carefully composed, and the final product is so carefully structured, that to some extent it might be surprising for some people how intuitive your process is. When you’re on the ground doing the actual reporting, are you trying to stave off ideas about what the eventual book might be so you can be open to what’s happening in front of you?

I might go in with preconceived notions of what the story might be, but you absolutely have to have your antennae out and let things flow the way they’re going to flow. I did the book Safe Area Gorazde about a town in Eastern Bosnia. When I went to Bosnia, I never thought I was going to go to Gorazde. People were going, and I thought, “Well, I might as well go and see.” Then it became the subject of the book because I fell in love with the place. When I get back, and I have all the material, then I become very organized in how I structure it. I’ve learned to do all those things that I couldn’t have imagined when I started out. I’ll index all my notes. It takes weeks. I transcribe all my own tapes, because I want to rehear things.

I’ve learned over time that it’s better to have a real solid structure to what I want to do. I write an entire script. From organizing my notes to actually completing the script, it can take weeks or even months. Then I start drawing. To keep things fresh, I never storyboard. If you see my script, it’s just words. If I have a brilliant idea for the future, I might put it in, but there’s no indication of what I should draw. Every day I get the script, I look at it and I say, “I’ll try to draw this section.” I will just invent on the page what I’m going to draw. I let that be the spontaneous part, because the process is so rigid otherwise.