This piece has been published as part of Slate’s partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

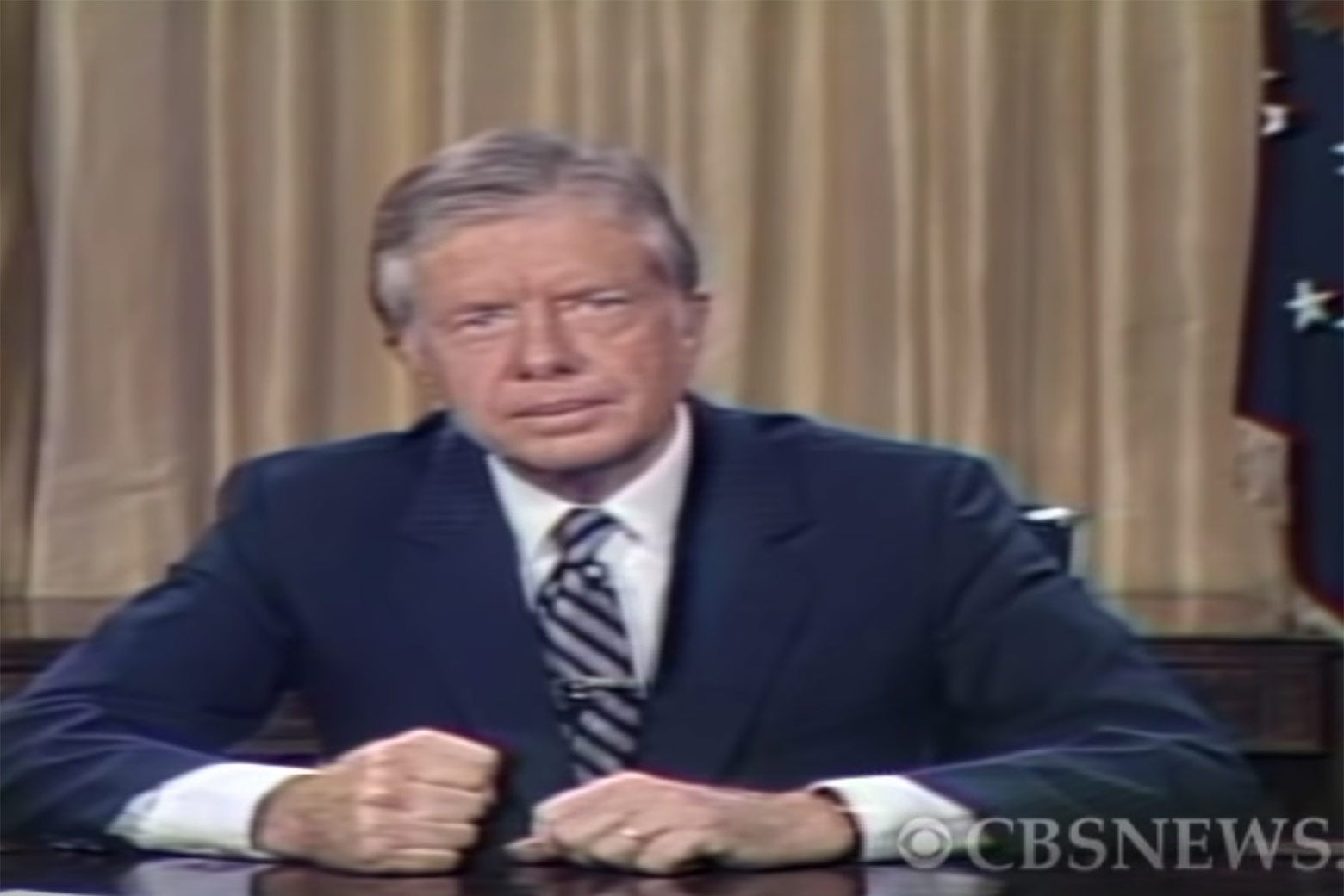

“Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns,” the president said. “But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.” No, this is not Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s 2032 inaugural address. It’s President Jimmy Carter speaking in 1980.

Carter used the same speech to announce “an extra $10 billion over the next decade to strengthen our public transportation systems. And I’m asking you, for your good and for your nation’s security, to take no unnecessary trips, to use carpools or public transportation whenever you can … and to set your thermostats to save fuel. Every act of energy conservation like this is more than just common sense, I tell you it is an act of patriotism.”

This address, which became known as the “Malaise” speech, was cited by 1980s champions of hyperconsumption as a key reason for Carter’s political demise. But it was well-received at the time—Carter’s approval ratings went up by 12 percentage points, with 61 percent of the public saying the speech inspired confidence.

The speech reflected the president’s broader approach. Carter had been committed to alternative energy (at least, alternatives to oil and gas; he supported nuclear and coal) right from the start. At his inauguration in 1977, the reviewing stand was heated by approximately 1,000 square meters of solar thermal panels. Later, he became the first president to install solar panels on the White House (these first ones provided hot water for the cafeteria, the laundry, and the family quarters). His administration vastly increased the budget for energy technology research and development to levels not equaled for another 30 years, until Barack Obama’s stimulus bill. He instituted the first tax credits for installing wind turbines and solar power, and set the goal of deriving 20 percent of U.S. energy needs from renewables by the millennium (so far we’ve made it to 9.4 percent).

Carter was not striking off in a bold new direction with any of these initiatives. He was reflecting the political mainstreaming of a movement that had been gathering momentum throughout the ’70s. The early part of the decade saw a raft of environmental legislation enacted during the Nixon administration: There was 1969’s National Environmental Policy Act, the Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970, and the Clean Air, Clean Water, and Endangered Species acts all passed over the next few years. Several states introduced container deposit bills to encourage recycling. All of this was relatively uncontroversial: There was still such a thing as moderate Republicans, and conservatism encompassed conservation.

The idea that the clock was ticking on the chance to avert a climate emergency was already part of the scientific consensus. Carter’s speech was greatly influenced by a 1972 report from the Club of Rome, a transnational think tank (members have included Al Gore, Bill Gates, Ted Turner, and, er, Marianne Williamson) called “The Limits to Growth.” It warned of “exponential” population growth and the potential collapse of civilization as we know it around 2100 due to resource exhaustion. The CoR has gone on to publish more than 40 subsequent reports on environmental issues, many of them climate-focused.

Just as scorching heat waves and unprecedented wildfires have made global warming more urgent in the wider public’s mind today, so two events in the ’70s moved the needle by illustrating the effects of resource scarcity on people’s actual lives. Between 1970 and 1973, U.S. oil imports more than doubled thanks to decreasing domestic production and increasing consumer demand. Then, in 1973, the oil-producing Arab nations imposed an oil embargo on the United States in retaliation for U.S. support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Gas prices soared and new phenomena appeared: long lines at gas stations (and, needless to say, fights), gas tank cover locks to prevent siphoning, consumers deserting their giant American cars in favor of the recently introduced less thirsty Japanese imports. As a conservation measure, Congress instituted a 55 mph speed limit on federal highways, prompting widespread protests including a Sammy Hagar song that declared, “Take my license, all that jive/ I can’t drive 55!” Stories surfaced of drivers of Japanese models being run off the road in oil-producing states like Texas.

The other pivotal event was the California drought of 1976–77, the state’s most severe water shortage of the 20th century, which prompted the public service message to “save water, shower with a friend.” (Newly elected Gov. Jerry Brown was even more committed to renewables than Carter: His tightening up of refrigerator regulations increased energy efficiency by a factor of one nuclear power plant, and he also offered 55 percent tax credits on wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass.)

The response to these events was increased awareness of environmental limitation. Greenpeace’s long campaign of direct action had just started—the organization was founded in 1971. There was also a social movement. California was the epicenter of the “back to the land” wing of the zeitgeist, an aspect of the hippie counterculture that channeled suspicion of the System into adopting a self-sufficient lifestyle (like survivalists, without the guns and paranoia). Some adventurous souls moved to communes to pool resources and share consumer durables like washing machines and cars. Their numbers were never large, but making your own clothes, wearing vintage, or recycling Goodwill finds were in fashion. Frances Moore Lappé’s bestselling 1971 Diet for a Small Planet popularized a diet based on vegetables, grains, and legumes, so the world’s grain supply would go toward relieving food poverty over feeding cattle.

A backlash was inevitable. Americans don’t like limits, speed or otherwise. Ronald Reagan promised them they didn’t have to have any. His “morning in America” framing assured the public that nothing needed to change and was presented as an alternative to Carter’s gloomy warnings. And, sure enough, under Reagan it was back to living as though resources were infinite. The research and development budgets for renewable energy at the recently established Department of Energy was gutted by nearly 90 percent, and tax breaks for wind and solar technologies were eliminated. A study underway at Carter’s Solar Energy Research Institute, later the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, to provide a blueprint for a renewables-powered energy future was defunded, and the institute closed down. In a symbolic gesture, Reagan dismantled and junked the solar water heater Carter had installed on the roof of the White House.

Fossil fuels, steak dinners, and conspicuous consumption were once again unquestioned norms. Instead of “living lightly on the earth,” the decade’s guiding principle was, as a popular bumper sticker declared, “Whoever Dies with the Most Toys Wins.” Despite numerous attempts to veer back toward Carter’s vision, we’ve never really returned. One thing is certain: Whatever road we’re on, we’re running out of it.